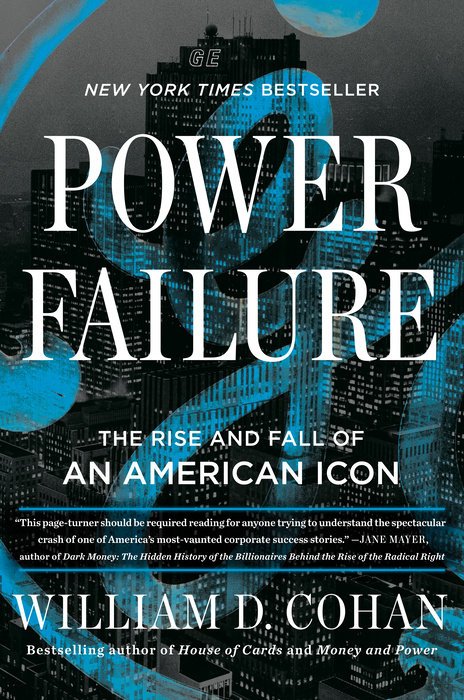

In his new book, Power Failure: The Rise and Fall of an American Icon, best-selling author William D. Cohan exposes the storied history of General Electric and its hard-charging CEO Jack Welch. Here, an introduction to the text from Cohan; an exclusive excerpt from the decisive chapter, “Habemus Papum,” can be found in PALMER Vol. 2, available now.

In the reporting of Power Failure: The Rise and Fall of an American Icon, my new book about the extraordinary rise and the incredible fall of GE, one of the world’s most valuable and most respected companies, I was fortunate to spend many hours interviewing Jack Welch. During his illustrious 20 years as GE’s CEO, the value of the company rose to more than $600 billion, from the $12 billion it was when he took over in 1981. In 1999, Fortune named Jack “Manager of the Century.” We met several times at one of his two golf clubs in Nantucket, a few times in his apartment in New York, and once, in 2019, at his beautiful home on Lost Tree Way in North Palm Beach, on a lake that was essentially part of the Intercoastal Waterway. He told me he preferred being on the Intercoastal Waterway to being on the Atlantic Ocean. At the exclusive Lost Tree Way development, home to many a fellow corporate titan, Jack told me he could swim in his pool and putter around on his motorboat, things he couldn’t do if he lived on the ocean. “It’s black, dark, and the wind blows,” he said of the Atlantic. (Soon after Jack’s death, in March 2020, his wife, Suzy, his executor, sold the house for more than $20 million.)

During our visit on Lost Tree Way, Jack talked about many different things, as we always did, including one of Jack’s favorite business maxims about the importance of what he called “wallowing,” where he’d gather a group of his top executives to hash out an important business decision. The buck stopped with him, of course. But he was willing to change his mind about doing a deal or not, or about making an investment or not, or reorganizing the company or not, if the “wallowing” was convincing enough. “Business and paradoxes are one and the same,” he told me that day in North Palm Beach. “You’ve got to constantly fight those instincts and look at every side of the coin.” He then shared an example of what would happen if he wanted to close a big GE plant in Louisville, Kentucky, the home to what used to be GE’s Major Appliance division. (It’s since been sold to Haier, a Chinese company.) “We’ve got an issue with closing a plant in Louisville,” he started. “The governor is apeshit—the governor of Kentucky. The union head is blowing his head off and he’s picketing in front of your building. You’ve got to get your team together. How do we reach a consensus? The union relations guy has got to speak up. The public relations guy has got to speak up. Everybody’s getting together and you wallow. You don’t make a decision overnight. And everybody has an equal voice, but no shrugs of the shoulders count. I always believed in that.” He then named two of his top direct reports. “Bob Nelson is a bright guy,” Jack continued. “Jim Bunt is a bright guy. They were instrumental in our success. The two of them would always have a contrary opinion on something and they’d speak up and they were thoroughly empowered to speak up. They were smart. They had a high IQ.”

The topic of the book excerpt, “Habemus Papum,” is how Jack went about making the most important decision of his career: choosing his successor. Jack chose Jeff Immelt, who then proceeded to lead GE for the next 17 years, ultimately resulting in profits and the stock price falling precipitously and the breakup of the company—much to Jack’s regret. It was Jack’s biggest decision and it was Jack’s biggest mistake, or so he would tell me every time we met, including again during my visit to see him in North Palm Beach. “Look,” he told me that day, as we were finishing up our lunch of tuna fish sandwiches on white bread, on the porch overlooking the water. “Anyone would have done better than the guy I picked. So, I batted zero; I batted zero. I said I got an A for running GE and an F for my successor, for picking that guy. The guy hoodwinked me.” Right about then, Suzy walked by, with her sister trailing. Suzy wanted to know when Jack and I would be finishing our conversation. Not anytime soon, Jack admonished her. Jack then pointed to Suzy and said about his mistaken choice of Immelt, loud enough for her to hear, “She knew it right away. She brags about being right on it.” Jack then insisted that what Suzy said next about Immelt be off the record. I reluctantly agreed to Jack’s request. But, trust me, on this and on many other issues, there was no daylight between Jack and Suzy. What follows is an excerpt from Power Failure, in which Jack makes the final fateful decision on who will succeed him at GE as CEO.