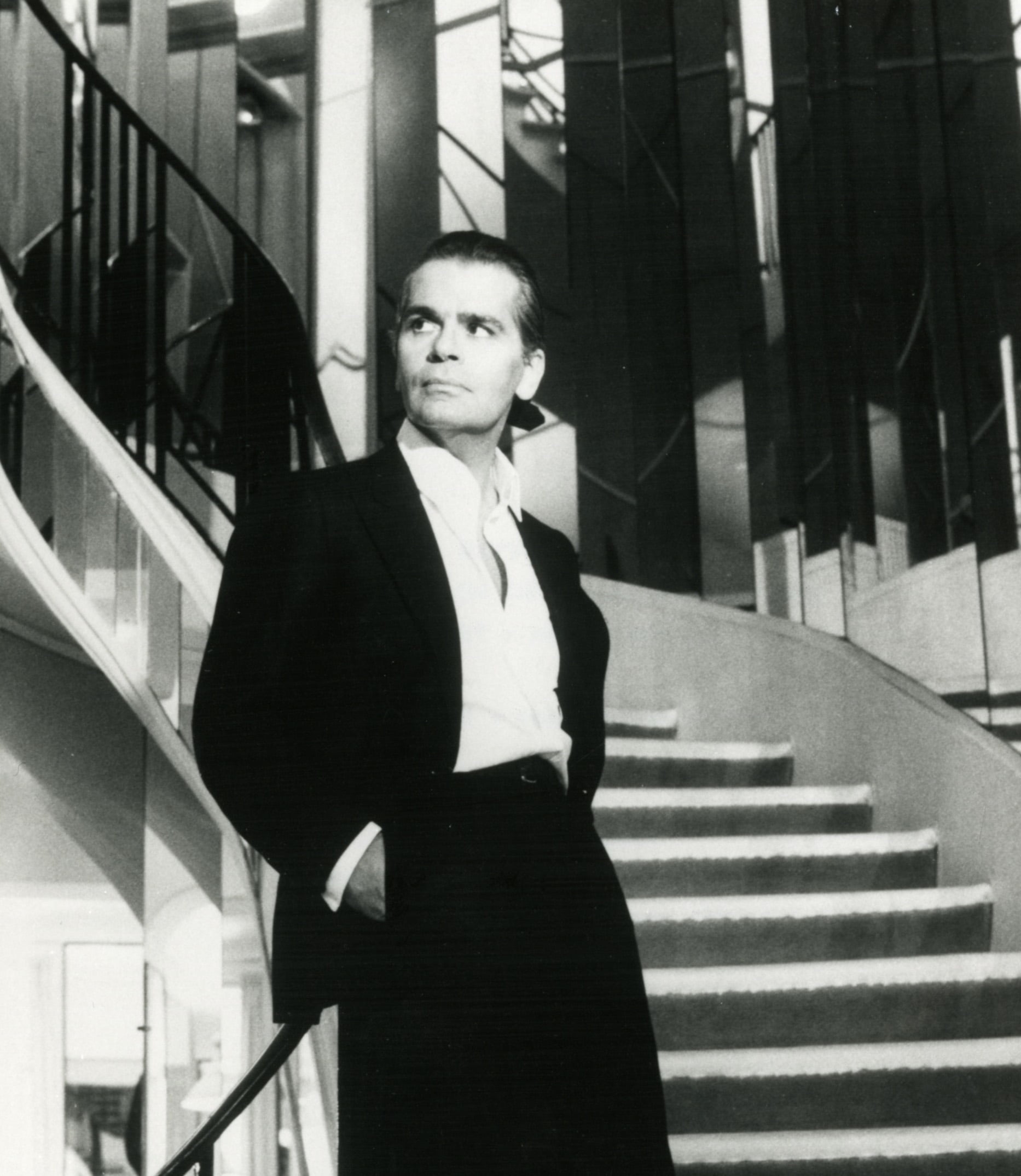

“I have three professions,” Karl Lagerfeld was fond of saying in his later years, “I’m a photographer; I’m a book publisher; I’m a fashion designer.” For more than three decades, Karl, as everyone called him, turned himself into an accomplished fashion and portrait photographer, while, for over two decades, working with the German house of Steidl, he published scores of exquisite books in a host of languages. But his work as a fashion designer, which he practiced for 65 years, from 1954 until his death in February 2019, was what made his reputation. Season after season, Karl showed his design talent at Fendi, Chloé, his eponymous label, and, beginning in 1983, the storied house of Chanel. But particularly in the last two decades of his life, Karl transcended fashion, managing to turn himself into a hyperkinetic polymath. He was an international cultural force, radiating creativity out through the worlds of art, cinema, music, literature, and image-making. There he was, staging a Chanel cruise collection and street party in Havana; pulling off a remarkable Fendi show on the Great Wall of China; or unveiling a special Chanel Métiers d’art show outside of Edinburgh, in the 15th century ruins of the castle of Mary Queen of Scots. (His time in South Florida tended to center around The Raleigh in South Beach, a hotel, and a scene, that he adored.) The fact of the matter is that, in recent years, there have been few others in the world—in any field—creating at his level.

I had the pleasure of first meeting Karl in January 1995, when I was the Paris Bureau Chief for Fairchild Publications, overseeing Women’s Wear Daily and W Magazine. Of course, our relationship was mutually beneficial. I represented two publications that were important in his world, and he was one of the leading figures in the Paris that I covered. But we quickly began to have a good working relationship, even a friendship. I was not, in any way, one of his best friends. But I always admired him greatly for his firm grasp of history and the intense connection he had with the culture of his day.

Karl never wanted to have a book written about himself when he was alive. The last time I saw him, in December 2016, I told him that I was finishing my first book, on the French/American art patrons Dominique and John de Menil, and that, after it was published, I wanted to talk about doing a book with him. His reaction was completely noncommittal, managing to shake his head both up and down and sideways while making the vaguest of sounds. Karl was horrified by the idea of anything that focused too much on his own past—to him, that kind of memorialization meant that life was over.

After he died, on February 19, 2019, Karl became a historical figure. I felt strongly that his impressive trajectory, and his multidisciplinary accomplishments, were too important not to be documented. So, for the last four years, I have had the pleasure of studying the life of Karl Lagerfeld and trying to put it into a narrative. I have interviewed over 100 of his friends and coworkers; reviewed the voluminous archives at Chanel, Fendi, and Chloé; and processed the incredible amount of interviews that Karl gave over the years. The result, Paradise Now: The Extraordinary Life of Karl Lagerfeld, has just been published by Harper Books. Here, a few flashes from his iconic journey.

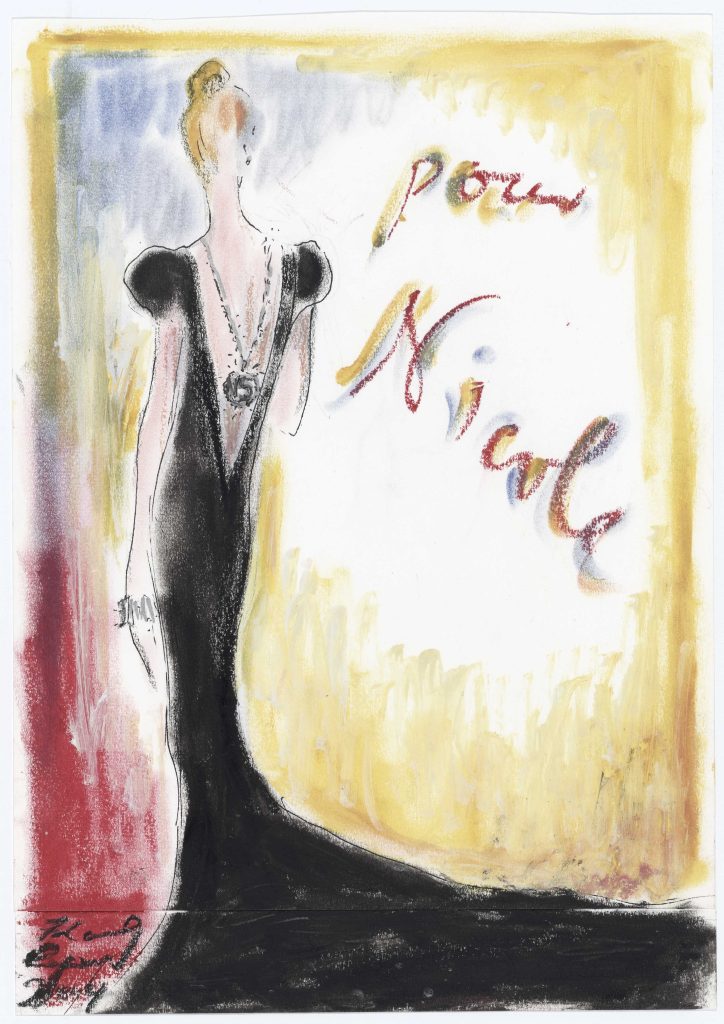

Karl’s drawing for Nicole Kidman of a Chanel haute couture evening gown for the Chanel N°5 commercial directed by Baz Luhrmann in 2004.

Radical Change

Karl began to amplify his international travel. In December 2002, he jetted off to Florida for Art Basel Miami, doing an exhibition with the Galerie Gmurzynska, a Zurich dealer of 20th century Modern art that he had had a relationship with for years. “When we first did shows with Karl, we got killed for being opportunists who work with a star who is not an artist,” recalled Galerie Gmurzynska director Mathias Rostorfer. “We were accused of doing this not for art but for publicity. When one knows the history of the gallery, it makes perfect sense because the Russian avant-garde, that Karl loved and we are famous for, did not make a separation between the fine arts and decorative arts. In Russia, in 1910–1920, female artists were absolutely equal to male artists, and theater design and a scarf design and painting and drawing were absolutely equal.” The first shows they did together had earned the gallery criticism from critics, clients, selection committees, and museums. “The more Karl established himself as a famous photographer, the more we got re- quests from, guess who, the top museums in the world,” Rostorfer continued. “Everybody, at one point, wanted a Karl Lagerfeld show from us.”

By 2001, clearly, the art world was more open to some Lagerfeld excitement. Rostorfer was asked by the director of the art fair if he could bring Karl to South Beach for the first edition of Art Basel Miami. Rostorfer asked Karl what he would think about doing an exhibition in a shipping container that would be positioned outside the fair. Karl had the exterior of the long, narrow container covered with huge blowups of his black-and-white photos of Berlin. Inside were wall-sized black-and-white prints, in red lacquered frames, of Hollywood stars Karl had photographed: Jack Nicholson, Nicole Kidman, Ryan Gosling, Meg Ryan, and Arnold Schwarzenegger.

To mark the occasion, Karl participated in an Art Basel Miami discussion about art and fashion with Ingrid Sischy [the Editor in Chief of Interview, who was one of Karl’s closest friends]. She wore loose black pants and an untucked blue Lacoste polo, while he appeared in tight white jeans, a sharply cut black jacket, a high-collared white dress shirt, and a skinny black tie with white diagonal stripes. His sunglasses were narrow, angular. Karl was dismissive about designers who try to consider themselves artists. “One category should never compare itself with another one,” he said. “Why would designers want to be called artists? They can be artisans. The world of art is another world. And it’s not exactly the same deadline—every six months.”

Karl and Sischy had a wide-ranging discussion about Russian Constructivism, the design of the Bauhaus, and Contemporary art. He pointed out that many fashion and textile designs of those early 20th century movements were not actually sophisticated, and that they were also far removed from all of the money that was now sloshing through the worlds of fashion and art. Karl suggested there was a certain tension between fine art and glamour. “Sophistication can take it away from the world of art,” he pointed out. “I think Andy Warhol was the first to find a way in the middle of it—but not everyone is Andy Warhol!”

Claudia Schiffer photographed by Karl for the first time, for the advertising campaign for Chanel Spring/Summer 1990. ©CHANEL

Revolutions

Friday, November 12, 2004 was the day that the man who turned Chanel into one of the most exclusive brands in the world—think of that impeccable, imposing corner boutique on Worth Avenue—went mainstream. It was the moment that Karl unveiled a capsule collection he had designed for H&M, the Swedish colossus, with $6.2 billion in annual sales, and thousands of stores in 19 countries. In the middle of the night Paris time, around 4 a.m., Karl called Donald Schneider, an art director who had worked with French Vogue who had first approached him about doing the H&M collaboration. Schneider, who was in New York on a shoot, received the call on his cell phone around 10 p.m. Karl had been excited about the H&M project, but now he was nervous. “What if nobody shows today?” he asked Schneider.

“He was worried that his career would be ruined,” Schneider recalled. “I calmed him down, telling him that, of course, it would be a success, even if I had my doubts. We all had such adrenaline in those last weeks—we thought we were onto something, but we just were not sure.”

Although Caroline Lebar, his longtime Director of Communications and Image at Lagerfeld, had initially been underwhelmed by the idea of a collaboration with H&M, she worked closely on every aspect of the project. On the morning of November 12, she was accompanying a journalist from Libération to the H&M store on the rue de Rivoli. They arrived at 7:30 a.m. Turning the corner on the rue de Rivoli, they saw people huddled together on the sidewalk, in sleeping bags. “We didn’t understand what was happening,” Lebar recalled. “We assumed that they were homeless. Only after a moment did we realize that they were camping out, waiting for the store to open. We said, ‘Whatever is going to happen, it’s going to be something that the world has never seen—that whatever is happening is something that’s completely crazy.’”

Lebar, the journalist, and the Libération photographer went into H&M to document the opening. From their first conversation, Lebar had told Karl that she thought the stores were a mess, but he had a sensible response. “If you know that the stores are terrible,” he told her, “all you have to do is specify in the contract that the place where your clothes will be shown has to be a place that is perfectly clean.”

As Lebar entered the H&M store, she understood what he had been saying. “The store was still a mess,” she said with a laugh. “But we went down the escalator, and there, straight ahead, was this Karl Lagerfeld corner: impeccable, beautifully lit, clean, all in black and white—it was magnificent!” They took some photos of the space for the newspaper and then took their positions, waiting for the store to open. Lebar was going to take pictures for Karl. “We see the doors open, and then people start running down the stairs—it was a stampede! I couldn’t take any pictures— we were literally run over by people. Five minutes later, everything in the corner was completely gone. I saw a guy get bitten. He was holding a cashmere coat, at like 80 Euros, and this lady wanted it back—she bit him—right in front of us!”

Lebar left H&M feeling that she had witnessed the beginning of something significant. She called Karl to let him know what had happened. “He answered as though he had been waiting for my call,” Lebar said. “We both said that it was fantastic, and it seemed that he knew that something big was happening, but he was also fairly calm. Perhaps it was because I had been opposed to the project and he didn’t want to take a victory lap.” Years later, though, she heard from Karl how important that call, the first indication of the success of the project, was for him. “I will never forget where I was when I received that call,” Karl said in an interview in front of Lebar. “It is one of those moments I will remember all of my life.”

By the afternoon in Paris, the morning in New York, one thousand people rushed into the H&M on Fifth Avenue in the first hour that the store was open. “He’s an icon,” said Marni Low, a 24-year-old New Yorker, as she grabbed $49 skirts and tops. The scene was repeated in big cities all over the world.

So much changed in the wake of Karl’s collaboration with H&M. A few weeks after, he went off to Tokyo for Chanel, and then to New York. On the streets of Tokyo, he was mobbed. From Japan, with 35 pieces of luggage, he flew to New York. Then he went back to Paris, flying Air France, in an Airbus A380. “In first class were Jean Paul Gaultier, Karl, and me,” recalled Sébastien Jondeau [Karl’s longtime bodyguard and assistant]. “I felt like I was at the heart of international fashion. Karl hated the flight because of some equipment in the flight attendants’ station that was beeping all night. I loved it all. It would be the last time that Karl took a commercial flight.”

Karl’s daily life in Paris also changed drastically. “I remember the date of November 12 so well,” Caroline Lebar recalled of the day the H&M collection dropped. “A few days before, it was possible to walk with Karl on the street, to stand next to his car—no problem. Starting on the afternoon of the 12th, that was no longer possible. It was all over—he could never again walk alone on the street.”

A fourteen-year-old Karl in the front row of his class photo from Bad Bramstedt, outside of Hamburg.

Courtesy of Gordian Turk.

Larger than Life

In September 2010, Karl flew to New York to accept an award and to celebrate the reopening of the Chanel boutique on Spring Street in SoHo. The Thursday night opening was a high-energy affair that brought out celebrities, the New York fashion crowd, and friends of Karl: Blake Lively, Sarah Jessica Parker, Diane Kruger, Sofia Coppola, Claire Danes, Russell Simmons, Liv Tyler, Peter Marino, Lynn Wyatt, and Cindy Sherman.

On Friday, Karl was at Avery Fisher Hall in Lincoln Center for a benefit luncheon for the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology. The museum awarded him the Couture Council Fashion Visionary Award. Karl wore a three-piece suit in dove gray, with a matching shirt and wide tie, with dark gray leather driving gloves, fingerless with little silver studs. Seated to his right were Anna Wintour and Amanda Harlech; to his left were Sandy Brant and Sischy. The award was given to him by Kruger. “Almost every woman in the world, from Kansas City to Kyoto, owns a piece of your design,” Kruger said, “And those who don’t, want to.”

On that trip, as he always did in those years, Karl stayed at the Mercer Hotel in SoHo. Saturday evening, he left for the airport with Sischy, in one of the black minivans that he preferred to use in New York. There had been a huge crowd gathered outside the Mercer, hundreds of people, perhaps as many as a thousand. Sischy said the scene reminded her of the crush of fans that greeted The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show. “All of these people waiting for a fashion designer, to get his autograph or to take a photo,” Sischy said to Karl. “What’s that like?”

“Well, it’s getting better and better, or worse and worse, depending on how you look at it,” Karl replied. “I am easy to spot—the white hair, the look. I am different from others—surely it’s that.” They discussed when this began, with Karl noting that he had been stopped on the street before, but also mentioning the H&M collaboration. “I think there is a connection with new technology,” he suggested. “Phones with cameras didn’t exist before. The whole system of communication has changed—my visibility increased with all of these new technologies.”

“You are the perfect symbol of our technological era,” Sischy pointed out.

“I’m not involved in any sexual scandal—I don’t sing—I’m not an actor. For me, this public fascination is a little strange. But I have become something like a virtual character—I’m an avatar.”

“How do you see your fans?” Sischy asked.

“They are not limited to any one generation or any specific age. One thing that I think is interesting, and flattering, is that many of those who shout, who stop me in the street, are young.”

“What’s that like?” Sischy asked.

“It makes me feel that I was right not to live in the past, not to look backward.”

“I would like to look backward, however,” Sischy said, turning to Jondeau. “What happened last night, Sébastien, outside the Mercer?”

“When Karl left the hotel, there was practically a riot,” Jondeau explained.

“How many people?”

“More than a thousand. They were pushing to get closer, trying to touch him, to get a lock of his hair, as though he were God.”

“What do you think of all of that, Karl, what does it mean to you?”

“I’m not God,” Karl replied, “but I am Good.” After a laugh, he said, “Sorry, Ingrid, but I’m the king of this kind of game.”

This excerpt and more appears in PALMER Volume 3, available now.