Palm Beach resident Eleanora Kennedy and her husband Michael saw the historical and artistic significance of The Highway Man movement years ago, leading them to become collectors of these important pieces.

“Michael loved their history. I loved the colors and the simple, crude but perfect frames,” Kennedy says. “We hung 17 of them in the cottage; it was our only art.”

Today, her impressive collection was amongst the pieces included in Manor Auctioneers and Appraisers’ “Holidays with the Highwaymen,” an auction of art from the famous Florida Highwaymen group of artists which included a piece from Mary Ann Carroll, the movement’s only woman, which hung in the White House under Michelle Obama’s direction.

For PALMER Vol. 2, award-winning journalist and PALMER contributing editor Tim Malloy wrote a feature celebrating these local artists, who got their start painting the rural landscapes of South Florida and selling their works to tourists at roadside stands.

Get a preview of the story below:

About 50 miles due west of The Breakers resort, The Everglades Club, the sprawling new Atlantic-facing mansions and the glimmering storefronts of Worth Avenue, Al Black stands atop the Herbert Hoover Dike, mixing reds and blues on his palette and eyeing a towering summer thunderstorm rising above Lake Okeechobee.

He is one of the last surviving Florida Highwaymen, a band of Black artists who came together nearly 70 years ago, painting impressionistic Florida landscapes of their childhood. Their work captured the rural Florida of the mid 20th century, before the malls and big-box stores, condo towers, and golf course communities began encroaching on hundreds of thousands of acres of pristine grasslands and wild scrub forests from the coast to the western reaches of Palm Beach and Martin Counties.

Like his fellow Highwaymen, Black grew up in the Jim Crow South. Discrimination was rampant. Work was hard to come by. Most were raised in the poorest section of Fort Pierce, a town 130 miles north of Miami, and came from similar backgrounds: descendants of slaves and migrant workers who worked the nearby bean and cane fields. Art was a release, a creative outlet, and a way to put food on the family table.

Shut out of established galleries, the Highwaymen took to the streets. They sold their work at traffic intersections and at roadside stops. Their raw materials were unsophisticated. They often made their own frames. And they were prolific. Black recalls sometimes selling ten paintings a day, the oil still wet.

They may have painted for money, but what evolved was a unique movement of young outsider artists, who established an entire visual catalog of the natural world around them. In the subsequent years, 25 men and one woman were welcomed into the tightly-knit artistic community. They forged their own path with no patrons and scant attention from the established art scene. But what was once seen as a postcard souvenir to remember a sun-drenched holiday is now a Florida treasure. Today those same $25 paintings command thousands of dollars at auction, and hang on the walls of Palm Beach’s stateliest residences.

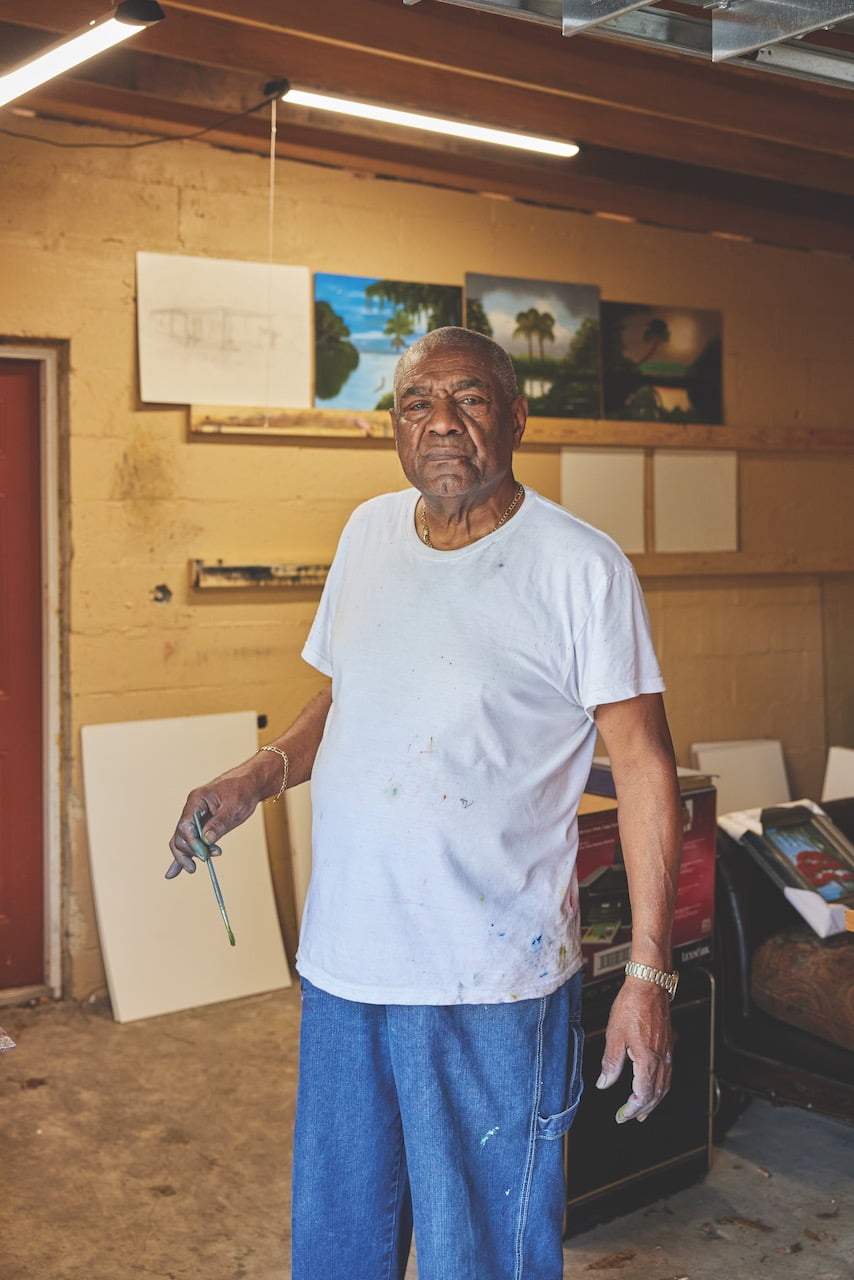

Al Black in his studio.

Looking out over the vast shore of Lake Okeechobee, Black works in delicate, quick strokes. On the canvas, reeds spring from a swamp illuminated by the reds and oranges of a quintessential fiery Florida sunset. Perhaps next he’ll paint the vibrance of the native summer foliage. “The Royal Poinciana tree is what made the Highwaymen famous,” he says, proudly.

The award-winning journalist, Tim Malloy, spoke to Black, one of the surviving Florida Highwaymen; Dan Hess, the chief curator of Florida’s Art and History Museum and an expert on the Highwaymen’s work; and Doretha Hair Truesdell, the wife of Alfred Hair, widely considered to be the founder of the group. Read the full story in PALMER Vol. 2, available now.