Walmart heir Rob Walton, 78, recently joined one of the most exclusive clubs anywhere in the world. Not the club of American billionaires, of which there are about 725 these days, and in which he is already a member, along with his two siblings, Jim and Alice.

No, he is a new member of an even more exclusive club: Owners of a National Football League team. In August, Rob Walton and his immediate family became owners of the Denver Broncos, one of the NFL’s 32 football franchises, after the other members of this tony club voted to allow Walton, his daughter, Carrie Walton Penner, and her husband, Greg Penner, to buy the team for $4.65 billion from the Bowlen family. It was the highest price ever paid for an NFL team. Walton, with a net worth of about $65 billion, became the wealthiest in a consortium of mostly white, male, multibillionaire NFL team owners.

But what made the Broncos deal particularly interesting—aside from the extraordinary purchase price and the involvement of the Walton family—was that a Black man had tried, and failed, to buy the team. A man of color vying to buy an NFL franchise would pretty much have been unheard of as recently as a decade ago. But there was Robert F. Smith, the founder of private equity firm Vista Equity Partners, with a net worth of around $9 billion. Word had it that he was interested in making a run at buying the Broncos. Given the hefty purchase price, it was unlikely that even the nation’s richest Black person would have been able to compete against Team Walton. But the very idea that Smith had tried was a significant sign of the times.

In the wake of the George Floyd tragedy, organizations across the country—media, corporations, universities, nonprofits—have begun to rethink how to diversify their ranks. Many industries have worked openly and decisively to begin the complicated process of addressing imbalances of power. But when it comes to the NFL, progress has been glacial. (It’s not just the NFL that’s been slow to the changing landscape; both the NBA and MLB are woefully underrepresented when it comes to ownership diversity.) The question is whether professional football, through a mix of its particular culture and valuations, considers itself immune to societal pressure. Or if it, too, will need to rectify its past.

To its modest credit, the NFL appears to be making a show of trying to change. At its annual meeting in Palm Beach last March, the owners approved a resolution to build more diversity among their ranks. “The NFL member clubs support the important goal of increasing diversity among ownership,” the league said in a statement. “Accordingly, when evaluating a prospective ownership group of a member club pursuant to League policies, the membership will regard it as a positive and meaningful factor if the group includes diverse individuals who would have a significant equity stake in and involvement with the club, including serving as the controlling owner of the club.”

And while the Waltons ultimately won the auction for the Broncos, they did invite two Black women, Mellody Hobson, the co-CEO of Ariel Investments, and Condoleezza Rice, the former Secretary of State, into the team’s investing group. “We think diverse organizations are more successful organizations,” Walton said at the time the deal closed. The Waltons’ first year as owners of the Broncos was rocky. Despite agreeing to pay quarterback Russell Wilson—one of 11 Black starting quarterbacks in the league—$245 million over five years, the Broncos ended 2022 with a record of 5-12, including a 51-14 drubbing on Christmas Day courtesy of the Los Angeles Rams that resulted in the Waltons’ decision to sack first-year head coach Nathaniel Hackett after the game.

The NFL began a little more than a century ago. Initially, the league was comprised of 14 teams across five states, with a geographic locus around Canton, Ohio, the site of the NFL Hall of Fame. White men—with names such as Ralph Hay (a car dealer), Carl Storck (a local Ohio football hero), Jimmy O’Donnell (a sports promoter), Stan Cofall (another local football hero), Frank Nied (the owner of an Akron cigar store), and Art Ranney (a local Akron businessman)—owned the teams and met in Ohio to form the league, which was first known as the American Professional Football Association. The idea behind the league’s formation was to try to “professionalize” what had been a haphazard collection of local and regional teams. Only two teams in the original league—the team that became the Chicago Bears and the team that became the Arizona Cardinals—still exist. George Halas, a former professional football player, moved to Decatur, Illinois, to take a job for A.E. Staley Mfg. Co., a manufacturer of starch, and served as the player-coach for the company-sponsored football team, the Decatur Staleys. They would eventually become the Chicago Bears, under Halas’ ownership. He paid $100 for the team in 1920.

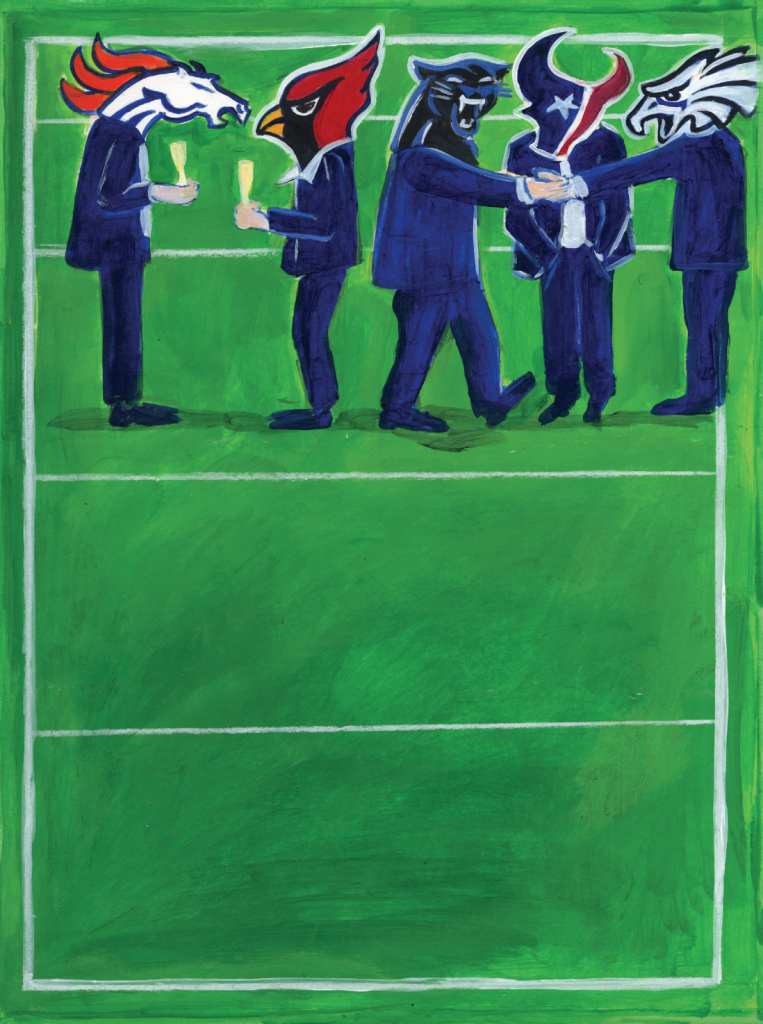

Ownership demographics haven’t changed much today. It’s still a club of businessmen. Only instead of being comprised of local small-time guys, these days the organization is made up of hugely successful multibillionaires. Coincidentally, many, including Robert Kraft, Jeff Lurie, Jonathan Tisch, David Tepper, Stephen Ross, Avie Glazer, Mark Wilf, Art Rooney II, and Woody Johnson, to name a few, are or were residents of Palm Beach.

Like many of the most storied clubs across the country, the NFL doesn’t look kindly upon new entrants, and must approve any sale to a new owner. There are also further restrictive rules, such as no corporate or governmental ownership of teams, or public disclosure of the teams’ financial performances. The principal owner of a team has to own at least 30 percent, and there can be no more than 24 partners in an ownership group. (One NFL team, the Green Bay Packers, has been owned by a large group of diverse shareholders, rather than a single individual or family, since its founding about 100 years ago.)

Kraft, the billionaire owner of the New England Patriots, is considered the dean of NFL owners, and is one of five white male owners who sits on the powerful NFL Chairman’s Committee. He bought the Patriots in 1994 from James Orthwein—the team was a long-struggling franchise—for $175 million. It was the highest price paid for an NFL team at the time. Kraft had made his fortune by marrying into a family that controlled a box manufacturer in central Massachusetts, and then parlayed that wealth into NFL ownership. His net worth these days, of more than $7 billion, is comprised largely of his ownership of the Patriots and his real estate developments in and around the Patriots’ Foxborough, Massachusetts, stadium.

Steve Tisch, the chairman of the partnership that owns the New York Giants, is a nephew of Larry Tisch, the former CEO of CBS who bought 50 percent of the Giants in 1991 from the founding Mara family, who continue to own the other half of the team. (The Maras created the New York Giants franchise in 1925, for $500.) Stephen Ross, the billionaire owner of the Miami Dolphins, is a Manhattan real-estate tycoon and the man behind the gargantuan Hudson Yards development on Manhattan’s West Side. He paid slightly more than $1 billion for the Dolphins in 2008. With a net worth estimated at more than $18 billion, David Tepper is the founder of Appaloosa Management, a hedge fund; he bought the Carolina Panthers in 2018 for $2.275 billion. Like Ross, Zygi Wilf is also a billionaire real-estate developer who decided to plow some of his roughly $1.3 billion fortune into the NFL; he bought the Minnesota Vikings in 2005 for $600 million. The list of extremely wealthy white owners goes on.

In fact, even though 70 percent of the players in the NFL are Black, there isn’t a single team owner who is Black, nor has there ever been a Black team owner among the more than 100 owners in the 102-year history of the NFL. There are only two current team owners of color: Shahid Khan, who owns the Jacksonville Jaguars, and Kim Pegula, who along with her husband, Terry Pegula, owns the Buffalo Bills. Khan, with a net worth of around $7 billion, is the owner of Flex-N-Gate Corporation, an auto parts manufacturer. He was born in Lahore, Pakistan, and moved to the U.S. at the age of 16 to attend the University of Illinois. Terry Pegula is a fracking billionaire, with a net worth of around $8 billion. His second wife, Kim, was born in Seoul, South Korea, and was adopted by an American family, the Kerrs, when she was five years old. The Pegulas live in Boca Raton, and own a variety of other upstate New York–area sports franchises, including the Buffalo Sabres hockey team and the Rochester Americans hockey team. Aside from the Green Bay Packers, every other NFL owner is either a white man or the wife or family member or child of a white man, who inherited the club upon their family member’s death, such as Sheila Ford Hamp, the principal owner of the Detroit Lions, or Virginia Halas McCaskey, the principal owner of the Chicago Bears.

Andrew Zimbalist, a professor of economics at Smith College (and the author of 28 books, including the 2021 Whither College Sports), looks at the NFL’s ownership problem as both one of economics and systemic racism. NFL teams rarely become available, and when they do, are quickly approaching a $5 billion purchase price. There are very few Black billionaires in America—and they are all self-made men and women, not hailing from generational wealth—so the pool of potential buyers in the Black community is exceedingly small. “For argument’s sake,” Zimbalist explained, “I’m going to say one-tenth of one percent of the billionaires in the United States are Black. Then the question is, if you go back 10 years ago, what percent was that and it was a lot less. If you go back 20 years it was a lot less still. But these are franchises, which are held for 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 years. And so, there’s just not that much opportunity for Black owners to jump in.”

The Steelers are owned by the descendants of Art Rooney, who in 1933 paid a $2,500 franchise fee to buy the team that is now worth billions. The Rooneys are also the namesake of the NFL’s 20-year-old, so-called Rooney Rule, which requires NFL teams to interview at least one minority candidate for a head coaching position and other top positions on NFL teams. (The Rooney Rule does not apply to owners.) Art Rooney II, the owner of the Steelers and the grandson of the team’s founder, is a member of the NFL’s Diversity Committee. No one from the Steelers would go on the record to talk about the lack of diversity among NFL owners, despite the fact that the Steelers’ highly respected head coach, Mike Tomlin, is one of three Black head coaches in the NFL, along with Todd Bowles of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and DeMeco Ryans of the Houston Texans. (Mike McDaniel, the head coach of the Miami Dolphins, is biracial.) The Steelers were also the team that hired Brian Flores, the former Black head coach of the Miami Dolphins, who Steve Ross, the Dolphins owner, fired in January 2022 after three seasons. (Flores later sued the NFL, claiming the Rooney Rule is a sham; he was hired by the Steelers as a senior defensive assistant coach.)

The subject of diversity has become such a thorny subject for the NFL that no one involved with the league or associated with an ownership group or a team would speak on the topic for this story. Even the NFL’s own Chief Diversity & Inclusion Officer, Jonathan Beane, did not respond to my request for comment. Their collective silence speaks volumes.

All of this begs the question: Why would anyone want to actually own an NFL team today? They are brutally expensive, of course; and like many other cultural touchstones, NFL teams, their management, and their owners are increasingly under the microscope and publicly held accountable for their foibles. Take, for instance, Daniel Snyder, the billionaire owner of the Washington Commanders. Snyder made his money from successfully running Snyder Communications, an advertising and media marketing company, and then selling it in 2000 to the French advertising conglomerate, Havas, for more than $2 billion. A year earlier, he had bought the Washington Redskins from the estate of Jack Kent Cooke for $800 million, at the time the highest price paid for a sports team. Snyder’s tenure owning the Washington NFL franchise has been rife with controversy, ranging from year after year of losing seasons; ten head coaches over 23 seasons; allegation of a toxic work culture; a defamation suit; and, of course, the ongoing, very public debate over the team’s name and whether it should be changed.

Of course, people want to own an NFL team because there’s simply so much money sloshing around, thanks to attendance records and mind-blowing linear television and streaming contracts. The new television and streaming contracts—worth billions and billions—have made NFL teams extraordinarily valuable assets, to the point where it no longer matters whether the team wins or loses; their value just continues to spiral upward. Amazon, NBC, CBS, ABC/ESPN, and Fox have all signed lucrative longterm television and streaming deals with the NFL. Amazon Prime, for instance, has an 11-year deal in place with the NFL to broadcast games on Thursdays, paying about $1 billion a year for the right to do so. Google’s YouTube just cut a deal with the NFL to stream “Sunday Ticket,” its weekly out- of-market games, for $2 billion a year. CBS pays the NFL $2.1 billion a year to broadcast games. Fox pays $2.2 billion per year; NBC pays $2 billion per season; and Disney/ABC/ESPN, $2.7 billion per season to broadcast NFL games. From Disney, Fox, NBC, and CBS alone, the NFL takes in $11.2 billion in annual revenue, and that’s just a start. There’s also local revenue based on attendance, concessions, merchandise, and various real-estate deals. This ongoing pot of gold gets divvied among the 32 teams based upon some magic formula that is kept very quiet. No one wants to rock the boat.

John Feinstein, the prolific author—his newest book, Feherty, about the golf commentator and former golfer David Feherty, will be published in May—wrote Raise a Fist, Take a Knee: Race and the Illusion of Progress in Modern Sports in 2021. He says that the NFL is still just a “billionaire’s boys’ club” whose members don’t think the rules apply to them. “The problem is they don’t really care about what the world thinks of them, because they’re ‘above all that.’ They think because they’re all rich—and in many cases, these are guys who were born on third base and thought they tripled—that they’re above the general rules of society.” He cited Snyder, the owner of the Washington Commanders, as a prime example. He held on to the Redskins team name until he was forced, by corporate America, to change it.

Owners aren’t operating in a vacuum. There are plenty who are complicit in maintaining the NFL’s status quo. If football fans didn’t go to the stadium; if millions didn’t watch at home sitting on their couches; if the media didn’t pay such huge amounts for the rights to televise or stream the games, then the league would be forced to change its ways. But viewers continue to tune in, and so the NFL plods ahead. Similarly, there are a whole bunch of hugely talented athletes who are willing to risk their lives for a whole lot of money, even if their playing careers average only about 3.3 years. The dangers of playing professional football were widely known well before Buffalo Bills starting safety Damar Hamlin collapsed, lifeless, to the ground on national television in early January. (That he seems to have fully recovered is not only a minor miracle but has also raised concerns that any serious debate about the safety of the game will be postponed once again.)

Despite the shock of Hamlin’s collapse; platitudes about the importance of diversity emanating from the owners’ meeting in Palm Beach; or half-hearted remarks from the NFL’s corporate office on Park Avenue, no great change is underway. After all, billionaires are not ones to use their power or influence to push for radical change. It’s usually quite the opposite.

Maybe Feinstein’s hunch—that soon owners won’t care who buys a team so long as the prices keep spiraling higher—will come true. Zimbalist, for one, wondered what the NFL owners would do if, say, the Saudis’ sovereign wealth fund, with more than $600 billion at hand, decided it wanted to buy an NFL team. Or what would happen if a corporation decided to make an offer for a team, even though the NFL charter bars that at the moment. Would the owners make an exception for the Saudis or for Apple in order to keep the prices rising? Or will they wise up and agree to take less than top dollar to diversify their ownership ranks? We’ll know relatively soon: Reportedly, all of the New Orleans Saints, the Seattle Seahawks, the Chicago Bears, the Los Angeles Chargers, and the Washington Commanders are rumored to be for sale in the foreseeable future.

This story and more appears in PALMER Volume 3, available now.