The paradise island is lost at sea due to overdevelopment, flashy investors, and $70 shrimp pastas. Michael Gross investigates the politics and the people behind the troubles to see if St. Barth can find its way back.

Roman Abramovich hasn’t been seen on St. Barthélemy since his superyacht Eclipse skedaddled just after Vladmir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. The oligarch’s $90 million Gouverneur beach estate still sprouts construction cranes, but Russian accents are no longer heard there.

Word has it that Larry Gagosian and Aby Rosen—two of the mega-wealthy early arrivals who turned the bay called Flamands into Billionaire’s Beach (Bernard Arnault’s Cheval Blanc is a relative hostelry in comparison)—rarely go out when they’re on the island. If Muammar Gaddafi’s son Hannibal visited again after Beyoncé and Usher played his private New Year’s Eve party in 2010, he’s kept it on the down low. And other one-time fixtures like hip-hop’s Russell Simmons and the financier Ronald Perelman have suffered setbacks that have kept them from conspicuous globetrotting. Yet longtime habitués of the renowned French Caribbean paradise do not lack for new things to complain about.

Take Laurence (not her real name), a designer, who has lived in the Hamptons and worked and vacationed in Palm Beach and on St. Barth for years. After her most recent visit, she’s had quite enough, thank you.

“I arrive, get into a car, and I’m mired in traffic looking at hillsides full of construction, there’s garbage all over, they’re spraying poison against mosquitoes, the beaches are covered in seaweed, and there are influencers taking selfies everywhere,” Laurence grumbles. “Nothing can be what it was, but what made St. Barth special was the French Euro casual chic thing—and it’s gone.” Crowded, often exasperating, anything but relaxed, and in Laurence’s words, “insultingly expensive,” St. Barth seems ever more endangered, and Laurence blames herself and folks like her.

“I know I’m part of the problem,” she admits. “I can’t stand to see what I’ve done.”

The invasive species that’s done the most damage to St. Barth since it appeared on the luxury travel map after Standard Oil heir David Rockefeller arrived in the mid-1950s? It isn’t the unprecedented 5,000-mile-long belt of sargassum algae now fouling beaches from Africa to Mexico. It’s people like Laurence, well-to-do sophisticates who “discover” a destination, only to get elbowed out by unsophisticated but even wealthier newcomers. In their wake come the unscrupulous, who would rather carve a golden goose than preserve it.

In St. Barth, that’s almost everyone: Land-rich locals tired of being cash-poor who sell their property to the highest bidder. Hospitality groups from Miami to Saint-Tropez and Paris to Boston, more interested in financial engineering in a lax regulatory environment than in being easy with their scene-maker clientele. Those clients, who flit like grasshoppers and can be as destructive as their locust relations.

And then, there’s that stunning French server, approaching your table right now, ready to upsell you to a magnum and demand a tip even though service is compris!

To those who knew St. Barth years ago, it all stinks worse than week-old sargassum.

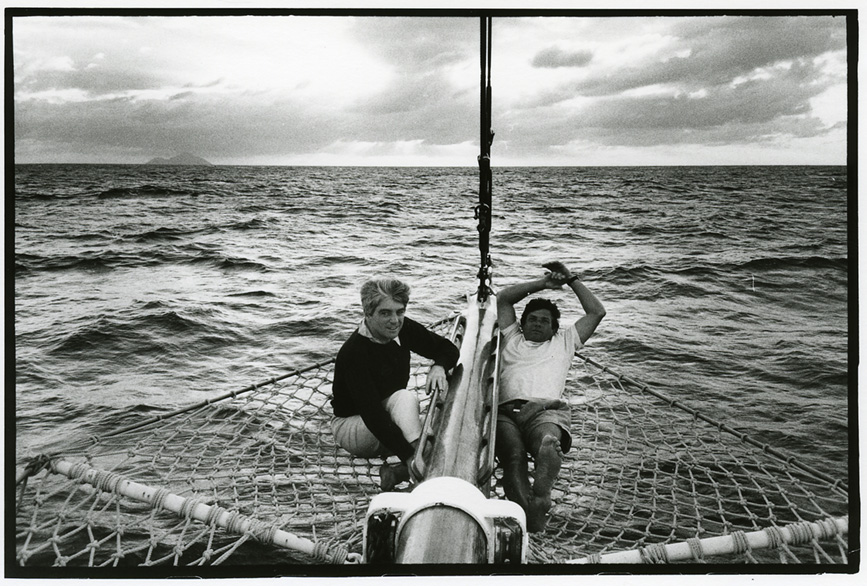

Martha Stewart and Jean Pigozzi, 1990

St. Barth in 1995

Just because your clientele is rich doesn’t mean they are smart. So in fits and starts for more than a dozen years, the citizens and government of St. Barth have squarely faced the challenges of success. The insouciant island is a microcosm, a window on trends in high-end travel and leisure; the rise and fall of destinations; the evolution of the jet set; the effects of concentrated wealth; the decline of social standards; and the ill effects of all of that.

For more than a decade, Rockefeller, who owned a 130-acre estate, and a handful of similarly wealthy or adventurous travelers had the place to themselves. Unlike neighboring islands, St. Barth never developed a slave economy because its lack of water and arable farmland meant it could not support cotton or sugar plantations. Though the French bought slaves, enslavement was abolished in 1847, and that tricky history was obscured years later by tourism advocates who promoted St. Barth as “safe” well into the 2000s—racist code for an almost all-white island. This signaling wasn’t all that set this least Caribbean of the Antilles apart, but it was disturbingly effective.

Into the late 1970s, St. Barth was a simple place. Determined travelers willing to endure the journey to an island serviced only by nauseating ferries or a tiny airfield which was, until 1984, little more than a shack and a short runway on a former goat pasture, were a particular, self-selecting elite. They disdained golf courses, high-rise hotels, gambling, and French music (Johnny Halliday and Juliette Gréco aside), and disregarded the island’s paucity of telephones, television sets, tennis courts, and any semblance of social life. Instead, they savored the 20 or so beaches; the dramatic landscape of peaks, flat savannahs, and long views across the Atlantic and Caribbean to St. Martin, St. Kitts, Nevis, and smaller off-islands; quaint, colorful island architecture; local sea and Creole-French food in a handful of markets and restaurants, and a special treat for American capitalists: Cuban cigars.

By 1980, the island had been discovered by mainland French folk. Disparaged as métropoles or locomotifs, i.e. city folk who set trends and move on, few stayed; island life was too simple compared to their chi-chi haunts in the south of France. And St. Barth pushed back against their influence; in 1983, hotels were briefly limited to a dozen rooms, though that soon rose to 80. But the arrival of those French tourists kindled a new entrepreneurial spirit in the island’s real elite—the dozen or so families descended from 17th century colonists who owned most of the land.

Encouraged by local officials, and aided by a handful of enterprising, island-mad Americans, they conjured up a tourist trade turbocharged by a unique hospitality ecosystem: rental villas were the island’s choice accommodation. The savvy chose homes over hotels, in the process lining the pockets of those local families, whose standard of living rose, and who could finally educate their children in Guadeloupe and Europe. They came back with worldly ambitions.

David Geffen, 1991

As the years passed, more tourists arrived—rising from a few hundred in 1963 to 100,000 a year by 1983, when the permanent population was a mere 3,000. In the mid-’80s, there were 100 rental villas, about 350 hotel rooms, and the island’s vehicle population had grown from 500 five years earlier to 4,000. In 1991, when the permanent population was over 5,000, there were 180,000 tourist visits and 700 hotel rooms. By 2007, the resident count climbed to nearly 8,500 and there were almost 324,000 visitors, filling ever-more extravagant rental villas, hotels designed by the likes of Christian Liagre, and international restaurants helmed by celebrity chefs like Pino Luongo and Jean-Georges Vongerichten. Land, worth about $125,000 an acre in the early 1980s, vertiginously rose in value. Today, one acre costs about $1.3 million. And there are now more than 800 rental villas with 2,500 bedrooms, 25 hotels, and 15,000 vehicles.

The island offered a unique blend of exclusivity, style, and refined debauchery that was unique to the Caribbean. For a few blissful decades, the crowd was as sophisticated as the scene was relaxed. Rothschilds lived above the bay of Marigot, Goelets on Gouverneur, Mikhail Baryshnikov atop Mont Lurin, Rudolf Nureyev on the rocky shore of Toiny—and they all mixed in the restaurants and bars. Fashion photographers shot all over the island and boat-hopped with models and designers in the port of Gustavia. On any given day, you could run into Calvin Klein on Salines; Lee Radziwill and Herb Ross outside the Casa del Habano cigar and panama hat store in St. Jean; Steven Spielberg, Kate Capshaw, Tom Hanks, and Rita Wilson at Maya’s; Lorne Michaels and Steve Martin at La Marine; and Caroline Kennedy Schlossberg and her kids in the airport. Or you could buy some blow at the bar of the Yacht Club and dance the night away at Autour du Rocher. It was expensive, but the experience was a worthwhile tradeoff. Over time, though, inevitably the good attracts the bad—stars who feel they need bodyguards and the gossipy media, like Page Six and the Daily Mail.

In 1995, Brad Pitt and Gwyneth Paltrow were photographed nude by paparazzi lurking in the rocks over their villa at Le Toiny, the island’s most remote hotel. By 2004, Perelman, Larry Gagosian, Simmons, and Puff Daddy were island regulars, and Le Pelican, the sandy-floored, wall-less St. Jean beach shack serving grilled fish and simple salads (albeit with langoustes), had given way to Nikki Beach, a link in a chain of haute beach clubs that began in Miami’s South Beach, where caviar and sushi are the norm for lunch. Money was everywhere, and Gustavia’s marina turned into a superyacht parking lot and plutocrat petting zoo.

In the 21st century, hillside homes of mahogany and teak, made obsolete by changing tastes or damaged by storms like Hugo and Luis, were muscled out by mansions of concrete, stone, and glass. The open, canvas-topped Portuguese Mokes and Jeep-like Brazilian Gurgels that had long been the island’s understated vehicles of choice, their low centers of gravity ideal for the roller-coaster roads, were replaced by Minis—and even the odd electric blue Mustang. Beach bars that once served beer and cheap and cheerful rosé now drown in Cristal. A year-old restaurant called Sella sells jeroboams of 2000 Chateau Lafite Rothschild for about $34,738. They cost $7,600 in a retail store.

Larry Gagosian, 2004

St. Barth won political autonomy in a 2003 referendum in which its residents, alongside those of neighboring Saint-Martin, shrugged off their former caretakers in Guadeloupe to gain the legal status of French overseas collectivités, transforming their mayors into presidents. The move for independence had begun in the mid-’90s, when local families began to fear that France wanted to change the tax-free status St. Barth has enjoyed since Sweden sold the island to Louis XVI in 1784. Instead of income tax, the Collectivity raises money with import, tourism, power, and water taxes.

Before that referendum and after its 2007 implementation, St. Barth swung into its age of bling. In 2003, André Balazs, operator of celebrity-oriented hotels in Los Angeles, New York, and London, briefly took one over on Grand Cul de Sac, a reef-protected bay. He was foiled in a subsequent attempt to build an eco-resort behind another beach, Salines, by the fervent opposition of three local environmental groups, which collected 1,200 petition signatures representing 15 percent of the population. But his moves were a dropped flag at the start of two decades of rampant development.

In 2008, a subsidiary of a London hedge fund owned by two Swiss businessmen bought a cottage colony on Grand Cul de Sac, and announced plans to build the $53.4 million Hotel Nilaia, but it was stopped mid-construction. The owners ended up suing each other and one of their passive investors. Mark Nunnelly, a former executive of Boston’s Bain Capital and CEO of Domino’s Pizza, and his wife, Denise Dupre, who’d worked in a family inn before becoming a hotel marketing professor at Ivy League schools, took over the project.

Renamed Le Barthélemy, the hotel opened in 2016. But the next year, it and the rest of the island were devastated by Hurricane Irma. Dupre not only repaired and reopened Le Barthélemy, in fall 2018, she bought another cottage-colony victim of Irma, the longstanding Emeraude Plage on St. Jean, the island’s most popular and accessible beach. They announced plans to replace it with a 20-foot-tall concrete luxury hotel. Though Dupre presents herself as a lifelong champion of sustainability, a plague of protests from island environmentalists ensued.

In 2019 and again 2021, Le Barthélemy was accused of dumping biological and chemical waste into Grand Cul de Sac, which is home to a bale of platter-sized sea turtles. Then, excavation began for a vast beach-adjacent underground parking garage at the St. Jean hotel, which Dupre named L’Etoile. Its opponents allied with the owners of Eden Rock, the island’s first hotel, right next door, who’d also tried—but failed—to buy the property.

On the wrong beach at a fraught time, Dupre became a symbol of rampant development. Two thousand seven hundred people signed a petition demanding L’Etoile be scaled back. One of her antagonists spray-painted “Get Out Dupre Pig” on the construction wall that still surrounds the hotel site. Finally, she was forced by a court order to fill in the hole dug for the garage. Dupre deflects when asked if she feels scapegoated. “Local governments have complexities,” she says, chuckling. “A pretty significant discussion happened on the island. We got caught in the middle” of what she calls “a bit of a crossfire that didn’t involve us.”

It did involve them, of course, but the issues went well beyond Dupre and Nunnelly.

Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas, 2004

The government of St. Barth’s five-term president Bruno Magras, who spent 40 years as a local office-holder, approved the Etoile excavation even though it had repeatedly tightened its planning regulations, most recently in 2020, “doing and redoing and redoing and redoing the map,” says Tom Smyth, who co-owns the island’s Sothebys International Realty. The rules now ban construction on 66 percent of the island, and limit coverage of the remaining buildable land to 15 percent. Capital gains taxes on real estate were also instituted to limit speculation and discourage investors. “We put the brakes on,” says Nils Dufau, Minister of Tourism in the Magras government.

A Charles Bronson lookalike with a pencil-thin mustache, Magras owned St. Barth Commuter, one of the local puddle-jumper airlines that serviced the island (since transferred to his children) and has interests in island real estate. He is rightly praised not just for establishing St. Barth’s political and economic independence, but also for developing its infrastructure and amassing land reserves of more than 100 acres, and “focusing development on high-end tourism,” he says. Magras acknowledges that “in recent years, St. Barth has become a victim of its own success. The economic and social balance of St. Barth has always been at the center of my concerns.”

Yet many believed Magras was Janus-faced, talking about careful, controlled growth (“There are limits,” he says) while enabling what the New York Times called St. Barth’s “hyper-development,” which created jobs and made some of his constituents rich, but also caused “traffic, water pollution, dead reefs, [and] housing shortages,” and pushed the island’s fragile ecosystem “to a tipping point beyond which it cannot return.”

That’s unclear, but it was certainly a tipping point for Magras. Reelected president with 74 percent of the vote in 2012, he found himself accused sotto voce of corrupt use of his power: arbitrary suspensions of long-standing “green zone” prohibitions (like allowing the 2018 addition of an elaborate beach club on a new hurricane-created beach at the tony Le Toiny hotel); conflicts of interest traceable to his various business interests, and the legal harassment of political opponents.

Magras dismisses such complaints as “simply denigration.” Yet, in early spring 2022, shortly after he announced his retirement (“The time had come to pass the torch,” he says. “I believe that people wanted a change”), Xavier Lédee, a former ally-turned-opponent, was elected the island’s second president, narrowly beating a cousin of Bruno’s. Hélène Bernier, the island’s highest-profile environmental advocate and development opponent, became first vice-president.

Alexis and Martha Stewart, 1990

The winners came from tickets explicitly combined to seek an end to what they termed the “abuses” and “excesses” of the Magras administration. But a number of structures that got building permits under Magras—it’s said there are hundreds outstanding, though permits can be for anything from new houses to walls and decks—are likely to be completed. They include a sprawling under-construction mansion looming over Flamands beach, owned by an Israeli-born British-American hedge-fund founder, investor, and collector of trophy art, Noam Gottesman. It was featured in social media ads for Lédee and Bernier’s campaign, under the bold slogan Stop ou encore?—Stop or more?

Sothebys’ Tom Smyth says of houses like Gottesman’s, “That’s not happening anymore.”

“They’re taking steps, slowing things down,” agrees the longtime manager of an island hotel. “It’s all got too much. I went to Sella and I wanted to cry. The island is still really special. It’s busier, crazier. It’s not ruined, but we’re at a saturation point.”

Development seems unlikely on the bay called Columbier, where David Rockefeller’s house was purchased in April for $136 million by its fourth owner, Adam Sinn, an energy trader from Texas based in another tax haven, Puerto Rico. Citing the property’s “one-of-a-kind attributes,” Sinn says he has no “firmly defined plans” for it, “other than a desire to renovate and restore” it quickly. Minimal changes are all the zoning rules allow.

Courts also recently ordered the revocation of permits granted by the Magras administration to a local family seeking to erect a concrete plant; to French real estate millionaire Patrice Cavalier to build a hotel and restaurant on Orient Bay on the island’s windward north coast; and to a local entrepreneur for a nearby multi-villa development on the former site of Autour de Rocher, a notorious five-room hotel-restaurant-disco that was co-owned for about a dozen years by musician Jimmy Buffett, who wrote a song about it:

“Every night at midnight / Seems the devil took control / And the hill became a parking lot / Fueled by rock ‘n’ roll.”

Autour de Rocher burned down, and after one last New Year’s Eve party in its ruins in 1991, it was bought by David Letterman. He sold the land in 2015 along with a permit to build a villa there, but it was deemed an insufficient basis for the developer’s bid to erect 24 homes.

Born on the island into a family that’s lived there for centuries, President Lédee was educated in France and Italy, and worked for Magras before deciding to run for president himself. He lost his first race in 2017, but won his second. He says development “has gone too far,” and though he hasn’t changed the zoning rules yet, he has tightened existing ones and plans to revisit the subject in 2024. “We’re not saying no construction, but we want to build smaller and take more time to build,” he says. “We have enough villas and hotels. We’re not able to host more tourists.”

Lédee praises his predecessor. “Bruno Magras put in motion a push for investment and economy. There is no other place with so few people and so much excess.” He doesn’t just mean wine and steaks, but rather St. Barth’s budgetary surplus of $83.4 million at the end of 2022. And France still pays to protect the island’s frontiers and for education and health care, though Lédee says both need improvement. He says the same about ongoing talks with Dupre and the Autour du Rocher developer. He wants to “ensure their projects match the island.”

Vows to change notwithstanding, buyers of buildable land still have the legal right to erect houses. And bling seems likely to remain a St. Barth thing. Last season, chartering a private plane from St. Martin that cost $350 in the ’90s was $1,190. A bottle of Ligne de St. Barth moisturizer that cost $19 two years ago was up to $37. A “special” cheeseburger at Gustavia’s Le Select shanty—which cost about $8.50 seven years earlier—was clocking in at almost $34. A grilled octopus tentacle at Gyp Sea, one of several new lunch clubs crowding the beach at St. Jean, is $42. A veal chop at the longstanding Italian restaurant in town, L’Isola, is $85. A tomahawk steak with mashed potatoes at the local Atelier Joel Robuchon will set you back $480. Chew on that.

David Geffen, 1990

Larry Gagosian, Charles Saatchi, and Leo Castelli, 1991

Irma marked a turn in the island’s evolution, but its reset is unresolved. It’s a story of yin and yang, of two St. Barths, one traditional (which persists, for those who know where to find it), the other symbolized by the ascendent hospitality groups that are buying and building new hotels, beach clubs and restaurants, and cater to what one local businessman calls “stupid money.”

It’s seen Maya’s, a beloved branché restaurant serving a market-driven menu of Creole-tinged French food, replaced by Sella, where a chef from Jerusalem lauded by Michelin offers Israeli cuisine—yogurt-marinated chicken for $51, shrimp pasta for $77, and a dessert called Chaos. Consisting of every sweet on the menu, served sans plates right on Sella’s tablecloths, it’s TikTok famous: guests gobble the gooey mess while the wait staff dances on surrounding tables. According to a complaint on the popular St. Barth Online forum, Sella is also where a manager made that “last minute and forceful demand for a tip,” which the poster compared to, “a Pimp collecting the evenings payments [sic].”

The simile isn’t entirely far-fetched. On St. Barth today, many, like Laurence the designer, are filled with regret over past sins against Paradise. Now, they say they’ve seen the light and want others to know it. Denise Dupre insists, “Everyone wants the same thing here, an island that continues to thrive. I loved the old St. Barth. Our family has vacationed there for more than thirty years. We are genuinely going to do our darndest to restore what was already there. We are.”

It’s all left David Zipkin, co-owner of Tradewind Aviation, which runs scheduled and private flights to St. Barth from Puerto Rico and Antigua, cautiously optimistic about the island that produces a fair share of its revenues. “There’s a right way and a wrong way to move forward,” he says over dinner at one of those holdout old school restaurants, Eddy’s Ghetto. “Stopping development completely is the wrong way. If it goes too far, though, no one will want to be there. Economic and ecological sustainability are intertwined. I’m not of the shut-everything-down camp, but there have to be limits. With a little bit of planning, and reasonable restrictions, the island can last many, many more decades.”

In a follow-up email, Xavier Lédee doubles down. “We won’t rest until things are better,” he writes. “We need to discuss with every economic actor to find together the right balance. Large investors come to the island and often have their own agendas. We can only succeed by all going in the same direction.”

Despoilers beware. There’s a new gendarme in town.

This story and more appears in PALMER On the Road, available now.