One night in early December, a colorful parade of women in long, full evening gowns and men in black tie glided up the stone stairs of the Metropolitan Museum of Art for the 25th anniversary of the Art & Artists Gala. Inside, the party (formerly known as the Met Acquisitions Gala) was filling up, with the similar frisson of the beginning of a very grand wedding. White roses stood at attention in large stone vases, while guests craned their necks this way and that to see who was talking to whom and who made the guest list—with attendees as varied as the artist Jennie C. Jones, billionaire Robert Kraft, model Karlie Kloss, David Geffen, and James and Nicky Rothschild. The bar was jammed as revelers jockeyed for Scotches and martinis.

Meanwhile, black dresses with tantalizing skin cutouts competed with silk; sequined kimonos and long hot-pink skirts practically screamed for the photographers’ attention. A light show projected twinkling snow on the north and south sides of the hall, and the entrance to the Temple of Dendur was lit with a come hither red glow. The design, by event producer Bronson van Wyck, was loosely based on the idea that art can light the way out of darkness—a nod to post-pandemic rebirth. Tiffany & Co. was a sponsor and, at $5,000 per seat, the gala raised more than $4 million for the museum.

The scene was New York power in its rawest and most physical form, manifested by the sheer magnitude of the event at one of the city’s greatest museums. Artists and benefactors mingled with fashion stars and high-wattage celebrities. To anyone present, it was clear that this august institution is greater than any one individual. But for this moment, five women could certainly take much of the credit.

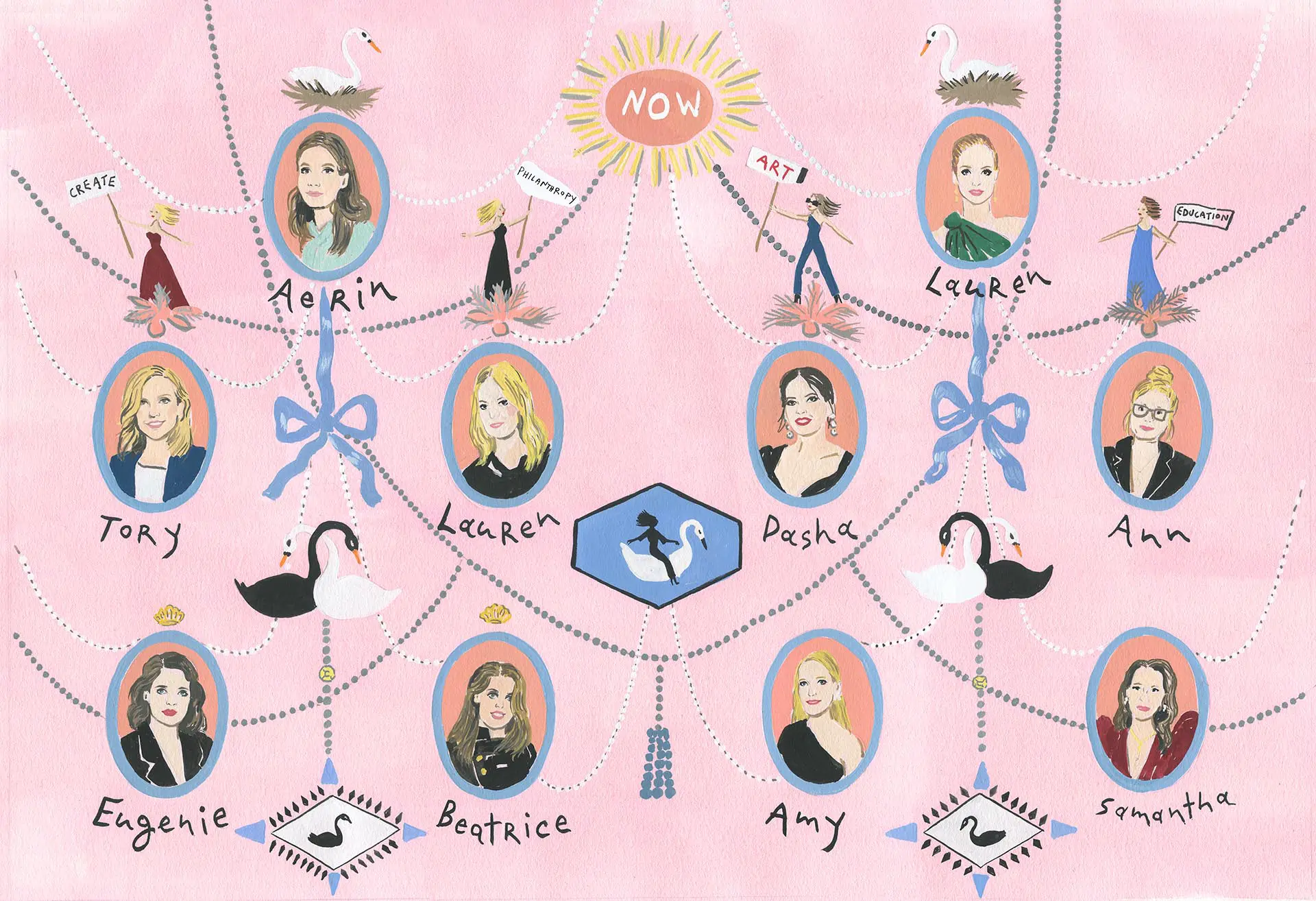

Posing for a photo with a temple column behind them were the co-chairs responsible for the evening’s success: Dr. Samantha Boardman, Amy Griffin, Gina Peterson, Ann G. Tenebaum, and Dasha Zhukova Niarchos. All come from divergent backgrounds, but they share a mutual passion for helping the institutions they love. The Art & Artists Gala was one of the buzziest parties New York had seen in years, but what made it especially unique was this particular group of women who had been chosen to lead it. They are today’s Swans, a term originally coined by Truman Capote to define the high-society women in his New York circle, those rare few who have the ability to draw others along in their wake. This new set looks surprisingly different from those who came before them.

“These women may be really beautiful, but they are paddling like crazy under the water,” van Wyck says. “Moving fast, selling tables, getting a lot done. Roping in all kinds of people from San Francisco, Chicago, Palm Beach, and Houston to help. There just aren’t that many people who can do that—and who can make it work.” Partially due to the pandemic, which hit New York and its cultural institutions particularly hard, as well as a general changing of the times, van Wyck adds, “The term Swans conjures up a certain kind of woman, but it really conjures up an era, and that era is gone.”

People raising money for the philanthropic institutions they revere is nothing new, nor is leveraging a certain kind of social fame into fundraising. But what’s different now in 2024, is that after having collectively experienced the trauma of the past few years, society had a moment to reflect on what institutions and events they really cared about. If 2020 was marked by endless Zoom meetings and online cocktail parties that seemed to have little real effect, at the very least it allowed people to strip away aspects of giving that were too scatter-shot, and instead focus on the organizations where they had deeper connections. And if the charitable system was to change, so would its fundraisers.

As opposed to generations past, these new Swans have confidence in themselves and their accomplishments. They have a broader range of friends, from artists to educators, rather than just sticking with those from similar backgrounds.

Most have had rewarding and remunerative careers where they learned to be leaders in their own right, before leveraging those skills to be successful fundraisers. Boardman is a Harvard-educated psychiatrist who runs a popular platform called Positive Prescription. Griffin worked in sports marketing for Sports Illustrated before becoming a venture capitalist who founded her own firm, G9 Ventures. Tenenbaum is an art-world powerhouse who sat on the board of the Dia Art Foundation from 1996 to 2006 and currently sits on the Public Design Commission as the Met representative. Peterson is President of The Peterson Family Foundation and a Trustee of SFMOMA. Zhukova Niarchos is a cofounder of the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow and founder of Garage magazine.

They are a competent group, and that comes across not only in their day jobs but in their ability to collaborate with one another. This was the second year they co-chaired the Met event. As Boardman says, “There is a level of excitement—confidence in each other. Nothing better than working with an extraordinary team, where you bring more to the table collectively than individually. They are having those exchanges, they are accomplished, and throw fun parties.”

To understand the significance of how these women got to where they are now, one needs to go back to the beginning, to the original Swans of the 1960s: Babe Paley, C.Z. Guest, Ann Woodward, Gloria Guinness, and Marella Agnelli. This group created the idea of harnessing a carefully crafted image in order to advance the greater good.

Technological improvements in photography, an increased ease of magazine printing, and a national craving for a return to glamour after World War II fueled the public’s obsession with these 20th-century women. Their every move was recorded and thousands of column inches were devoted to their clothes, lifestyle, travel, and designer choices. A keen understanding of the value of appearance is a chief attribute of the Swans.

While some decried their use of publicity, breaking the old-school convention to only be seen in the press at “birth, marriage, and death,” their high profiles brought attention and money to their philanthropic causes. Charitable giving has always been a large part of how society operates, but the near-obsession with these stylish women burnished the idea of a philanthropist to such a degree that its gloss has never diminished.

However, their place in society and sense of self was, in large part, dictated by who they married. Perhaps because they felt anxious as they were not truly in control of their financial destinies, the women’s marriages were famously rocky. As a gang, they were a highly competitive, brittle collective who behaved more like business associates than true friends. It was an insulated life, and they were an insular group who were not especially welcoming to newcomers. When they weren’t dining at each other’s homes or at charity functions, they were at Mortimer’s restaurant on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, which functioned as their de facto club. Eventually, the crowd migrated further uptown to Mortimer’s one-time maître d’ Robert Caravaggi’s Swifty’s (now Swifty’s in Palm Beach). The Swans gossiped endlessly about each other; occasionally their poisonous remarks filtered back to the recipients, feeling even more animosity. Capote learned as much when he exposed their secrets in his 1975 Esquire article, “La Côte Basque 1965.” (A television series by Ryan Murphy called Feud: Capote Vs. The Swans, depicting their precarious friendships, is out now on FX.)

By the time the 1980s rolled around, a new crop of social leaders had emerged, including designers Carolyne Roehm, Carolina Herrera, Annette de la Renta, and Mercedes Bass. They were just as good at getting column inches as their predecessors, but their parties were bigger and bolder as they embraced the flamboyant excess of the period. The bigger the bank accounts, the more the women shrank in size, and the more exaggerated their lives became. The term “Social X-Ray” was coined by writer Tom Wolfe to describe the extraordinary emaciation that was considered the height of 1980s chic—their slim waists reinforced by the excessive shoulder pads of the day. They barricaded themselves with their wealth, maintaining their households with the same rigid discipline as their figures.

By the 1990s, after the “correction” of the stock market crash of 1989 and a subsequent recession, a slightly more sober social butterfly emerged. Tory Burch and Aerin Lauder were the beautiful young breakout stars of the decade and highly sought after, as Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar competed for stories on who decorated their houses and which clothing designers they favored. Unlike previous generations, these ladies were the first to successfully parlay the public’s interest into billion-dollar eponymous lifestyle brands that catered to the masses. By appearing to pursue the same life of leisure as the earlier Swans, playing tennis and drinking iced tea on the porches of their large estates, they made customers feel that they, too, could touch this rarefied world. In 2004, Burch launched her mega hit “athleisure” concept in an homage to that way of living. (In 2008, Burch used the proceeds of her newly acquired fortune to buy Westerly, the iconic 15,000-square-foot estate in Southampton—famous for the night when Fernanda Wanamaker Wetherell’s 1963 debutante party got so out of hand, all but six of the 1,600 windows had to be replaced.) In 2012, Lauder launched Aerin, a lifestyle brand comprised of fragrance and beauty products inspired by flowers and her artisanal finds.

Despite endlessly photographing their homes and lifestyles, the ‘90s Swans allowed the public only a peek into their private world. It was never an open invitation, and the mystery was always preserved. Children were kept mostly out of view, and personal questions, such as those about their spouses, were a no-go. They created the blueprint for global recognition, known as much for their ability to market and monetize their image as their ability to draw a good crowd.

While Burch and Lauder were perfecting their upright glamour, another Swan from a different period was taking a very active and different approach to charity. Brooke Astor became one of New York’s most beloved—and recognized—philanthropists, not only for her generosity to the New York Public Library but also for visiting the poorest neighborhoods in New York in pearls and a Chanel suit. No stranger to a spot of publicity herself, Astor openly championed the practice of on-site visits rather than staying in the boardroom. When asked why she always dressed up, she replied, “People expect to see Mrs. Astor.” She was also fond of saying “Money is like manure; it’s not worth a thing unless it’s spread around.”

At the dawn of the 21st century, when the internet and social channels began to replace magazines as the new way to extend reach, the rules of society had changed once again. Personal brands became the rage, and no one in New York understood that better than Lauren Santo Domingo. On social media, she honed the persona of the ultimate Gramercy Park icon, with her classic good looks and carefully assembled fashion choices, which were artfully downtown, but always ladylike. Never one to fall into the “slobs like us” category of many a fashion influencer (except for one memorable COVID moment when she too succumbed to buying a pair of sweatpants). Santo Domingo’s real genius is in her wit and good humor. Approachable even in couture, she gives off the impression of the cool girl to seek out at a party, one who would give you a big hug and welcome you into her circle of friends. To date, she has almost half a million followers on Instagram and, in addition to co-founding Moda Operandi, an online fashion retailer in 2010, she was also named artistic director of the Tiffany Home collection in 2023.

Post-pandemic, approachability may be the biggest difference between the Swans of yesteryear and those of today. As van Wyck notes, “The brilliant thing about New York society is that it continually regenerates itself. It always welcomes new people.” This current group does not need to stand on ceremony, and they’re perfectly willing to get their hands dirty.

In January, Boardman invited a group of her friends (including Griffin, her Art & Artists co-chair) to a birthday lunch she gave at Citymeals on Wheels in the Bronx. A fleet of Ubers and black town cars arrived at the packing center, creating a traffic jam among the warehouse’s 18-wheelers, as about 60 men and women arrived to pack meals for the homebound elderly in New York. For the next hour, some of the most socially prominent women in the city, including Jessica Seinfeld, Jill Kargman, Net-a-Porter founder Natalie Massenet, and Serena Boardman (Samantha’s real estate–powerhouse sister) happily nattered away to one another while putting together kits of carrots, apples, and soup for delivery. Afterwards, the guests took their seats at long tables. They dined on a feast of tuna melts, french fries, and strawberry milkshakes.

If only the Babe Paleys of then could see these women now.