In 2011, golf legend Tiger Woods moved from near Orlando to Jupiter Island, a barrier beach 25 miles north of Palm Beach. In 2005, he’d bought a 12-acre estate there for $44.5 million and spent $15 million more renovating it. He surely knew what he was getting into. It’s a place with a lot to offer but many complexities to navigate.

There are many private golf courses in and around Hobe Sound—57 within a 15-mile radius on the mainland, just across the Indian River section of the Intracoastal Waterway from lush, tropical Jupiter, according to Golf Digest. Leading the pack of celebrated and celebrity-friendly, championship-quality links are Medalist, where Woods is a member; E.F. Hutton’s Seminole Golf Club; Michael Jordan’s Grove XXIII; Greg Norman’s Jupiter Country Club; and Jack Nicklaus’s The Bear Club, as well as Donald Trump’s Nicklaus–designed Trump National; and Admiral’s Cove, where Donald Trump Jr. and Kimberly Guifoyle live in a $9.7 million home. The last three are private residential club communities, high-end real estate developments boasting the expensive amenities that sporty, high-net-worth individuals demand.

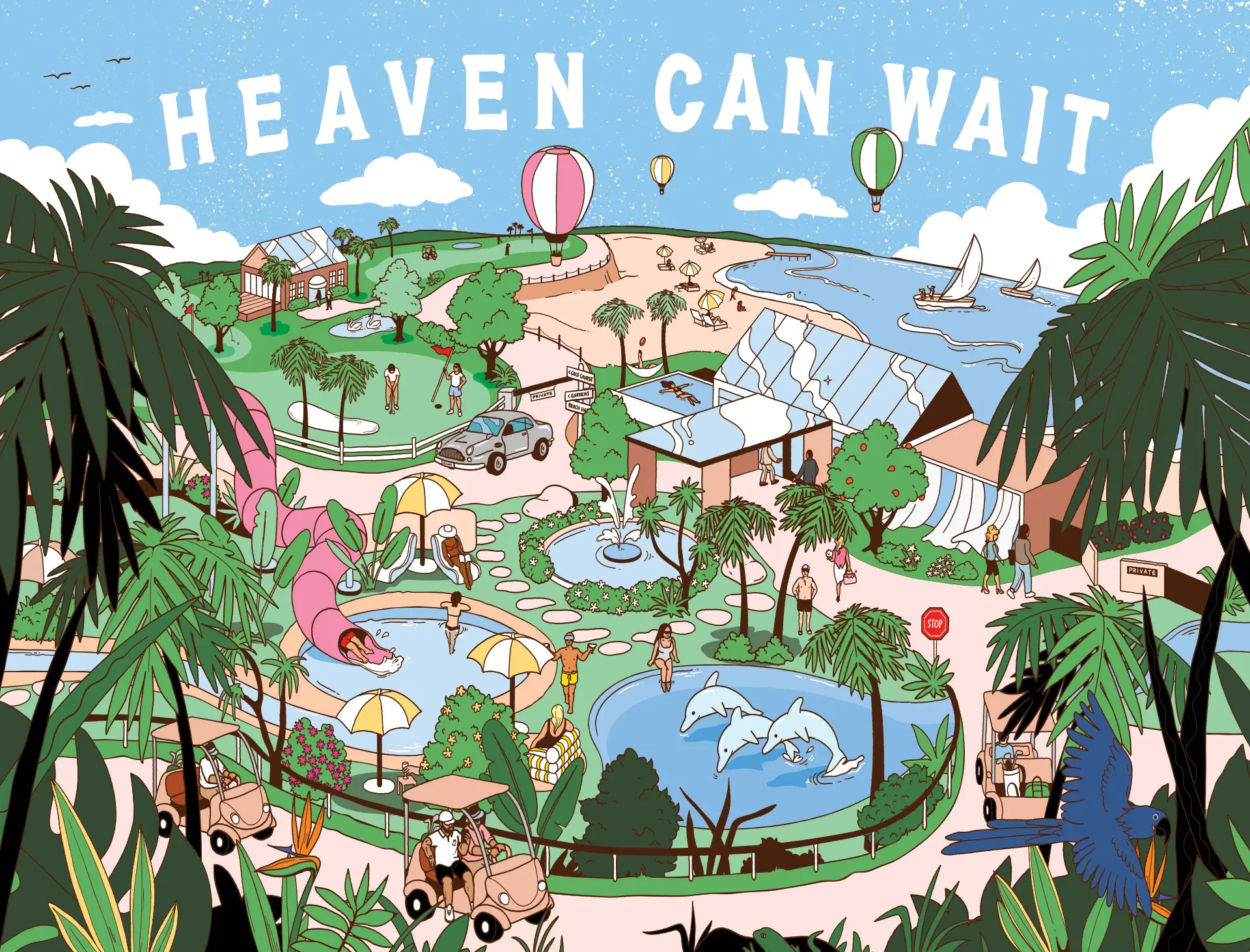

Where once communities walled themselves off with insurmountable standards, from landed family names and multi-generational connections to a particular religion or sex, today’s burgeoning gated neighborhoods are open to all—all who have multi-millions to spend on luxurious new-build homes, club dues, and an appreciation for planned communities. Whether because owners seek a sense of belonging or simply enjoy the benefits of an all-inclusive development, many of America’s wealthiest are now living behind moats and drawbridges. From the financial elite and tech vanguards to older business leaders and celebrities like Woods, who often serve as human billboards, membership in one—or more—of these club properties is proof of one’s importance. From the outside, depending on the view, it either looks like a democratization of status or a redefinition of tribalism. But with a lot more toys.

Strictly speaking, gated communities are nothing new. Indeed, The Jupiter Island Club, with a clubhouse a mere 10 minutes’ drive from Woods’ home, is eight decades old and long epitomized what the historian of wealth Cleveland Amory called, in his book The Last Resorts, “the social islands,” America’s “most formidable social resorts,” tightly guarded, inaccessible enclaves where residents are “so extremely well off that nobody tries to impress anybody with money.” But in recent years, they’ve become the ultimate real estate prize.

Woods is not a member of Jupiter. Some say he didn’t want to join. But he is an owner of a similar enclave. In 2005, Woods invested in Albany, a 600-acre resort community on New Providence Island in the Bahamas, founded by Joseph C. Lewis, a British-born, billionaire developer, currency trader, and sports and hospitality entrepreneur. And now, though he isn’t a principal, Woods is a neighbor of what’s being touted as the greatest gated residential fun park in America.

Discovery Land Company, developer and operator of more than 30 such communities around the world, is gearing up to open two more. Its founder Mike Meldman became a celebrity himself as the lord of famous and famously secretive resorts like Big Sky, Montana’s Yellowstone Club; Baker’s Bay in the Bahamas; and El Dorado in Los Cabos, Mexico, where he and next-door neighbors Rande Gerber, the club owner husband of Cindy Crawford, and George Clooney invented the Casamigos tequila brand. (Later sold for $1 billion, the brand owes its name to their Cabos properties.) Discovery’s roster of owners and investors has included Goldman Sachs, partners in the private equity giant Silver Lake, the Endeavor Agency’s Patrick Whitesell, Bill Gates, Apple’s Tim Cook, Nike’s Phil Knight, Tom Brady, and Ben Affleck.

Now, Meldman has set his sights on Florida. He hopes to have the first of two new projects fully operational by 2025. Atlantic Fields is a 1,500-acre golf and equestrian resort development on a former orange grove in Hobe Sound. Atlantic Beach is its oceanfront condo equivalent. This one-two punch bowl of delights, Discovery boasts, will combine “the refined elegance of ‘Old Florida,’” i.e. places like the Jupiter Island Club, “with a modern carefree ambiance” more likely to appeal to tech and finance moguls, young CEOs, and celebrities like Woods, who is a vital link in the chain connecting the hideaways of yesterday’s powerful and privileged with those of today’s more diverse and relaxed rich.

Offering luxury, privacy, and the pursuit of affluent sportsmanship, these once rare, limited-access retreats are now a phenomenon, symbols of the most compelling trend in luxury real estate.

They range from Lyford Cay in the Bahamas, which predated neighboring Albany by half a century, to much newer Discovery communities in Costa Rica, Mexico, southern Dubai, and Portugal’s Comporta; Birnam Wood in Montecito, Hidden Hills and The Estate of the Oaks north of Los Angeles; Las Vegas’ The Ridges; and Indian Spring Ranch in Wyoming; Agalarov Estate outside Moscow; and the soon-to-open Six Senses Residences in France’s Loire Valley and Discovery’s Taymouth Castle in central Scotland.

The new communities in Hobe will fit right into the evolving landscape, though Meldman’s spokesperson insists they are in a class by themselves. “Every developer is trying to copy us, but can’t,” she says, before adding that, especially in a post-COVID world, “the new status symbol is membership.”

The earliest example of elite havens erecting fences, separating the haves from their have lessers, was Tuxedo Park, located in the Ramapo Hills north of New York City, on land acquired in 1814 by Pierre Lorillard, a tobacco merchant. In 1885, Pierre IV took it over, and transformed 7,000 of his inherited acres into a bastion of formality, a fenced community-slash-club accessed by a private train station on an otherwise public line by member-residents with historic monikers like Astor, Goelet, and Schermerhorn. Its amenities included a clubhouse, lake, a toboggan slide, a golf course, and, most notably, facilities for court tennis, the world’s rarest and most aristocratic “racket” sport.

That island in the mountains—which still exists, albeit with much-diminished social and financial cachet—was quickly followed by others, equally inaccessible, in Maine (see Northeast Harbor), off Connecticut’s coast (Fishers Island), and then, in the Roaring ‘20s, in Florida, where an alternative to Palm Beach situated on Jupiter Island (but long called, simply, Hobe; both names derive from Jove, the Roman god of thunder). This destination island was conjured up by a group of English investors who built a small hotel and three cottages in 1916, called the Island Inn. During the Great Depression, the island was taken over by a Colorado banking and mining heir, Joseph Verner Reed, and his wife Permelia, whose father had been president of Remington Arms. They controlled the club, much of the island’s land, and more on the mainland, until Permelia died; her family sold the club to its members in 1996.

The offspring of Tuxedo and Hobe are many and varied, and are spread across America and, of late, around the world. Some remain exclusive in the sense of designed to exclude, but more and more prefer to be seen as merely elite, meritocratic, even democratic in word if not deed, though the demos, or people, who inhabit them tend toward the kratos, or strong, i.e. the winners of the world.

Jupiter Island has no gates; it doesn’t need them. Only two bridges connect its small network of roads to the mainland, and its attentive police force regularly deters interlopers. Before COVID, Florida’s Treasure Coast and Palm Beach County were already home to three other significant—and gated—club communities that attracted a fashionable crowd: Lost Tree, just north of Palm Beach, established in 1959, and John’s Island and Windsor, which opened, respectively, 10 and 30 years later on one of the barrier islands across the Indian River from Vero Beach.

John’s Island and the 450-acre Lost Tree Village, founded by E. Llwyd Ecclestone, Sr., a developer from Grosse Point, Michigan, began with luxury estates surrounding a golf course. Today, owners of its 524 homes on gently curved, elegantly landscaped streets share lakes, docks, clubhouses, restaurants, tennis courts, a fitness center, swimming pools, a chapel that doubles as an event space, and its own medics, plus human and K-9 security.

Newer club communities like Discovery’s and Albany also address the dilemma posed by the old template, where buying homes and club memberships are separate transactions. “You could sell to anyone, but anyone dumb enough to buy property first could kiss their chance of being members goodbye,” says a woman who gave up Jupiter Island for Lost Tree. The latters’ members include Jamie Baxter of Putnam Investments; Home Depot’s Ken Langone; food and beverage billionaire Jude Reyes, and Jack Nicklaus. The late Jack Welch was also a longtime member.

Meanwhile Albany’s facilities reflect its diverse membership: a recording studio that’s been frequented by Drake, Cardi B, Alicia Keys, Sting, and the Rolling Stones; a 71-slip deep-water marina big enough for superyachts like Lewis’ 323-foot Aviva; dry dock boat storage, a boutique hotel, a Las Vegas–style adults-only party pool, water playground, a boutique hotel, and nine places to drink and dine. There are also round-the-clock concierges, doctors, ambulances, ATMs, and a movie theater. Other habitués are David Beckham, Tom Brady, Patricia Hearst, Good Morning America’s Michael Strahan, and, until recently, the crypto-criminal Sam Bankman-Fried.

Lewis, Albany’s founder, began his career building theme restaurants in England, before moving to Lyford Cay, as he branched out into golf-centric community development at the Isleworth Country Club outside Orlando. He bought the property out of bankruptcy after building a home there in 1990. It gained fame when Woods bought a house there in 1996, the same year Lewis bought Lake Nona, another planned community in Florida. The pair and partners announced plans for Albany a decade after that. It opened in 2010.

“It ranges from traditional architecture to modern Bjarke Ingels homes,” Vickers says. The owners are “low-key overachievers.” She adds that safety and informality are also selling points. “In London, I live off Cadogan Square and I can’t go out wearing jewelry or a watch. I can wear whatever I like at Albany. I can go to dinner in my PJs if I choose. The only rule is: No photos of anyone.”

Actually, there are more rules, but they’re unstated, and insiders say violators can be asked to leave for offenses ranging from privacy incursions to the use of intrusive tech. But the successful new gated communities look at life through a 21st-century lens; they’re exclusive and expensive, but not exclusionary. And they seek to engage residents however they can, which requires more than golf.

Shari Liu Fellows, a luxury brand consultant, and her husband, who works in private equity, own a home at Albany and are building their next on the 18th hole at Atlantic Fields. “We’re all about Discovery,” she says. “Nothing is missed, no expense is spared. There’s luxury at every turn. They think of everything. Obviously, they cater to the .01 percent. At any moment, you’ll be next to Cindy Crawford or Adam Levine [of Maroon 5]. It’s a perfect combination of luxury, hedonism, and understated but serious competitiveness.”

Raising the amenities ante has become an arms race; club communities need something for everyone.

That gets expensive. But the business model allows for extravagance. Early buyers, often marquee names, are rewarded with bargains, but help developers break even. When prices go up later, profits roll in. Buyers are vetted, but with subtlety. “It’s not five letters and fifteen cocktail parties,” says a principal of one gated community. “There is some getting to know you. But it’s definitely easier than getting into Seminole or Maidstone.”

Like Discovery’s Meldman, Lewis has also created a foundation to win friends and invest in the communities where he builds. But their origins are quite different. Lewis’s father owned the London pubs where his son waited tables. Meldman’s was a lawyer who sold insurance in his native Milwaukee before moving his family to Phoenix. Mike dealt blackjack at a Lake Tahoe casino, became a real estate broker in Fremont, California, began making deals in Silicon Valley, and got an education in development when he bought 300 acres in a Stanford suburb. He spent the next 18 years building 28 homes there, a process slowed by environmental regulations and a depressed real estate market.

By the mid-’90s Meldman was back in Arizona, where he dreamed up a golf-and-hiking resort called Estancia on a mountainside outside Scottsdale, and sold its homes to tech types, who helped convince him that dress codes and rules against cell phones were obsolete, making bikinis and cargo shorts acceptable golf apparel. Discovery Land took off, and Meldman fine-tuned his formula, adding activities designed to appeal to his children (he is a divorced father) and inspired by the locales where he built—from Hawaii to Montana, surfing to fly-fishing. Meldman also bought properties out of bankruptcy, like the Yellowstone Club, which boasts its own ski resort, in Big Sky, Montana, in 2008, and took on equity partners instead of debt. Then, COVID made Discovery’s self-contained communities irresistible bubble worlds at the intersection of self-protection, self-absorption, and self-indulgence.

A world-champion networker, Meldman cultivated financial types who gave him access to more funds (like Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon, who owns a home at Discovery’s Baker’s Bay in the Bahamas and a condo at its Silo Ridge in Amenia, New York; Goldman was Discovery’s equity partner at Chileno Bay in Mexico) and celebrities who raised the profile of his properties. Discovery then sold more homes to their friends.

And now, there are Atlantic Fields and Atlantic Beach, Hobe’s new anti-Hobes. Atlantic Fields is a partnership with the family-run Becker Holding Corporation, whose 15,000 acres of orange groves and citrus processing operations produced 12 million boxes of fruit a year before disease decimated the crop and the company turned 800 acres into a tree farm, sold 1,800 acres for the Hobe Sound Polo Club, partnered with Jordan on Grove XXIII, and then with Discovery to erect 317 homes on 420 acres. Under the terms of a controversial 2022 amendment to the Martin County comprehensive zoning plan creating a new “rural lifestyle” designation, Becker left 2,300 acres undeveloped for recreation, agriculture, and wetland protection and restoration and open-space conservation. “This is how rural Florida disappears,” grumbled a local environmental group, “death by a thousand comprehensive plan amendments.”

Tom Hurley, CEO of Becker, who worked on the landscaping of Discovery’s Baker’s Bay property in the Bahamas, got to know Meldman better on Jordan’s golf course, where both are members. Hurley acknowledges local concerns. “Growth and development are the third rail in Martin County,” he says, but believes Atlantic Fields will help, not hurt, by offering a model for responsible change. “Only super-expensive development can support the [land] set-asides and amortize the costs of infrastructure,” he explains. “This is the lowest-impact, highest-value development imaginable.” The only municipal service Atlantic Fields will depend on, he claims, is Martin County Fire Rescue.

Vacant lots start at $3 million for Discovery’s “friends and family,” and rise to $15 million, valuing the Olson Kundig–designed development at $1.5 billion. Club memberships begin at $200,000 and annual dues are estimated to run $55,000. Building lots range from .33 to 4 acres and are clustered into mini-neighborhoods of estates, properties for equestrians near the stables and smaller cottages and homes beside the links and eleven lakes, as well as 2- to 4-bedroom suites in a clubhouse. There are 18- and 9-hole golf courses, equestrian facilities with stables and club-owned horses, a family park with court game facilities, a working organic farm, a store, a fire pit, access to hiking trails that connect to an adjacent state park, and a spa. A prospectus for buyers lists 21 separate sports available to owners, ranging from deep-sea fishing and polo instruction to a climbing wall and pickleball. It adds that beach access, presumably at Atlantic Beach, isn’t yet available.

Atlantic Beach was conceived after billionaire Jeffrey Soffer’s Fontainbleau Development (owner of the eponymous hotel on Miami Beach, the JW Marriott Miami Turnberry Resort & Spa, Turnberry Ocean Club Residences, and Marina and Turnberry Isle Country Club), bought two adjacent properties on Beach Road in Tequesta in 2022. They are on the southern tip of Jupiter Island below the Palm Beach County line. Martin County bars condominiums, but the Tequesta beach is lined with them. One of two existing ‘60s-era condos has already been demolished, and plans have been filed to replace both with 10-story buildings containing a total of 60 apartments. Talks are ongoing about sharing amenities with Atlantic Fields.

Fontainbleau is now gearing up to sell Atlantic Beach 1, designed by Swedroe Architecture (at 300 Beach Road), but a source close to the development predicts Atlantic Beach II at 250 South Beach Road (with preliminary designs by Arquitectonica) “will never happen” in its current incarnation, and remains “way off in the distance.” So Atlantic Fields swimmers may have to depend on their club’s and the family park’s pools for the time being.

Mike Meldman likely needs not worry. As long as the world keeps minting new billionaires, he’ll have fresh pools of buyers for his luxurious properties and their promise of profligacy and indulgence walled off from prying eyes. The old model epitomized by Tuxedo and Jupiter Island “is dead,” says a member of Lost Tree. “Old money is no money.” And money, finally, is what this residential phenomenon is about, both for those buying into them and those who build them.

“So many people want to come to Florida and it’s hard to get into the established clubs, so it’s a great economic opportunity,” says a retired Wall Street CEO from his home in Lost Tree. Adrian Reed, Jr., a grandson and heir of Permelia and Joseph Reed, and a member of the Jupiter Island Club, moved off the family’s island just after it was sold, and now lives just down the road from Atlantic Fields. “These guys came to my hometown. That’s how I look at it,” he says. “There’s nowhere left to build in Miami-Dade or Palm Beach County.” Yet snowbirds keep flying south, their beaks full of gold.

Reed’s biggest worry is controlling supply so new construction doesn’t threaten the fragile ecosystems that attract buyers in the first place. Like it or not, low-density communities for the wealthy strike many, including Reed, as an acceptable way forward. Discovery’s members may not resemble those his grandmother chose, but certain values align. “Keep the sky dark,” Reed says. “Keep habitats for critters.” So, development has moved west toward the wildlife and environmental preserves around Lake Okeechobee. “If it wasn’t controversial, it wouldn’t have taken so long,” Reed says. “But it is a turning point.”