Growing up on the north end of Palm Beach in the years following World War II, Mimi Maddock McMakin could scamper out the door of Tree Tops, her family home, and ramble through the property’s 14 lakefront acres. “We never had neighbors, we just had jungle,” McMakin recalls of the estate. “If something fell off a tree and it was able to sprout, it grew.” It was an idyllic childhood, spent riding bikes, fishing, and making mischief. Little did she know then that this house would become the place she’d raise her own family, and one that would shape her illustrious interior design career and cradle her own daughters and grandchildren.

This enchanted world was homesteaded by McMakin’s great-grandfather, Henry Maddock. Born in England, he emigrated to New York, from whence he traveled down the Eastern Seaboard, selling china produced in his family’s factory. Around 1891, a boat landed him on the shore of Lake Worth. “He liked it,” McMakin recounts.

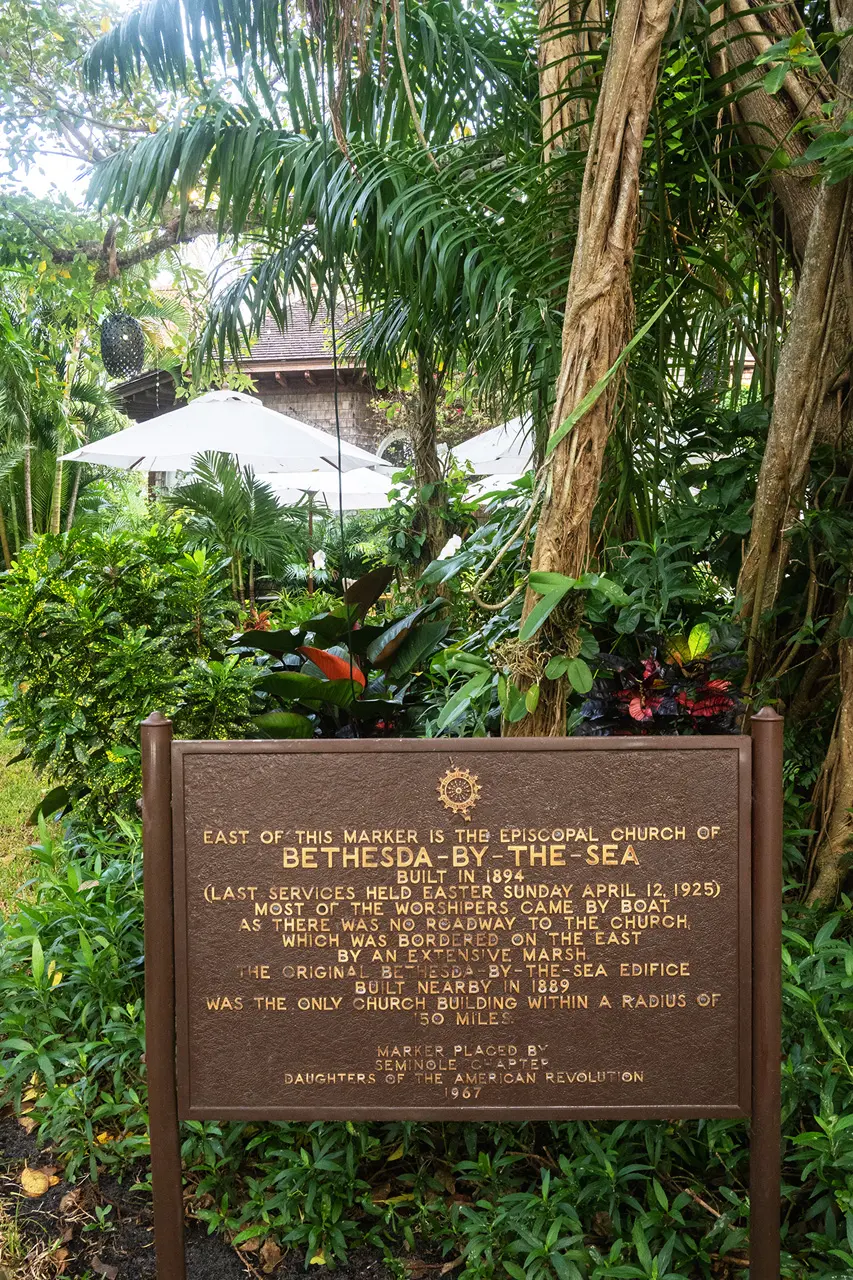

First, Henry erected a gabled Victorian cottage from prefabricated pieces barged down from the Northeast on inland waterways. He called it Ducks Nest— “Duckie” being his wife Jeanne’s nickname. The Church of Bethesda-by-the-Sea, a cedar-shingled Gothic-style building, soon rose nearby. A few decades later, when the church moved to its present location on South County Road, the Maddocks absorbed the deconsecrated house of worship into their lush compound, which by then also included Tree Tops, a rambling Adirondack-style house constructed by Henry and Jeanne’s son, Sidney, who in 1902 opened the 400-room Palm Beach Hotel, one of the town’s first resorts.

In 1974, the old church became McMakin’s home. She’s been putting her unique stamp on it ever since. Arguably, it is Palm Beach’s most original residence. And she, one of the town’s most original characters.

As a descendant of the area’s earliest pioneer settlers, McMakin, 76, could have lived out her days as a remaining vestige of Old Palm Beach and its privileges. Yet, in the early 1980s, a time when virtually none of the young women in her peer group worked, McMakin rolled up her sleeves and opened Kemble Interiors. Forty years on, it is one of the town’s most successful businesses.

“She’s part of the fabric of Palm Beach,” says lifelong resident Kate Gubelmann, who has known McMakin since their elementary school days. “Like Lilly Pulitzer, Mimi is one of those people who’ve been here for generations and really understands the culture. She has sustained Palm Beach style in a contemporary way. She hasn’t replicated the past, she’s taken the town forward.”

“She specializes in charm,” says Pauline Pitt, another longtime friend. “When you think of Mimi, you think of great fun. But sometimes that covers up how brilliant she is.”

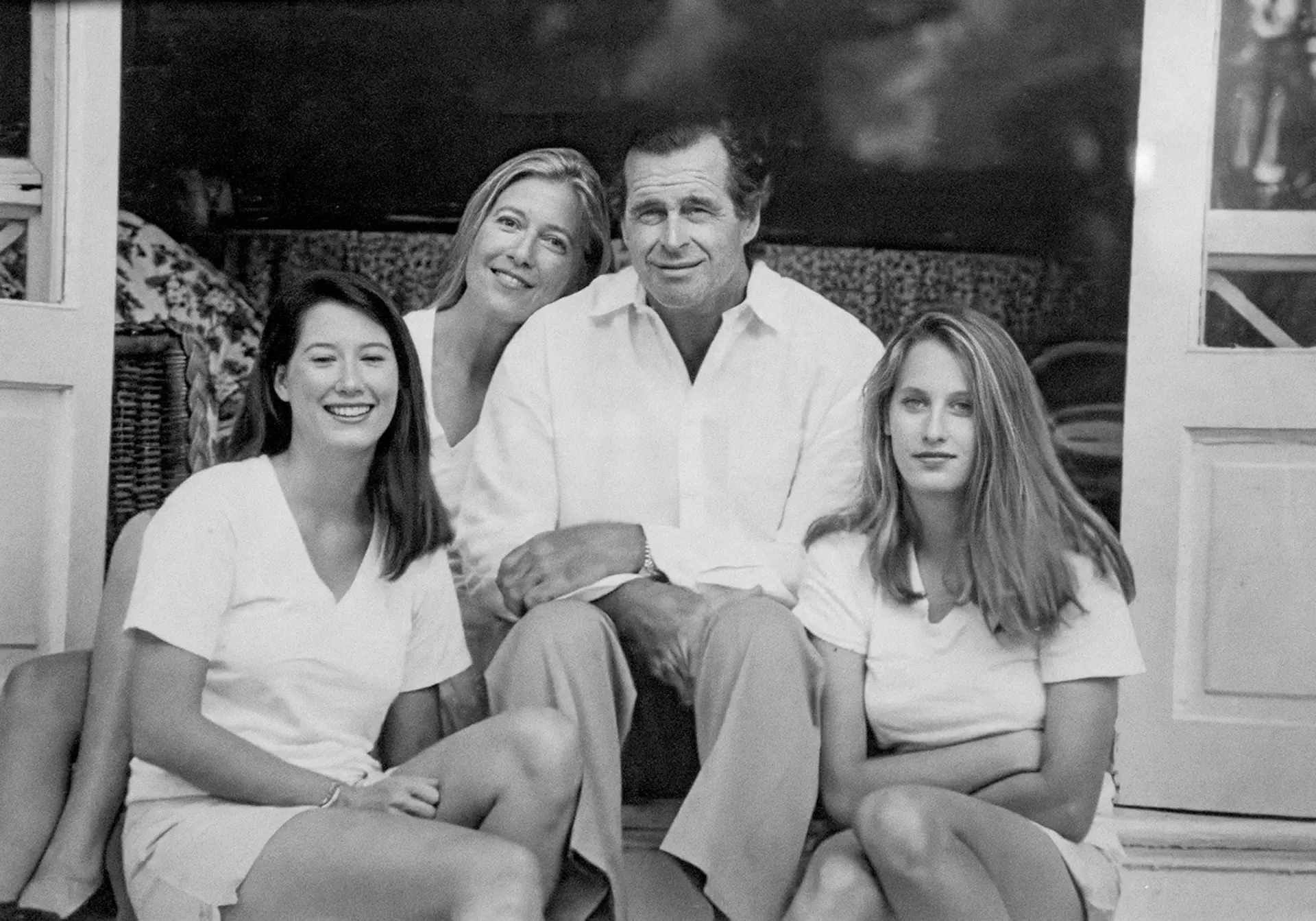

“Everything is sort of whimsical,” McMakin says with a laugh as she welcomes me into her home on a blustery Sunday morning in early January. She is referring to the exuberant décor, but could just as easily be describing the facts of her life, including how, 34 years ago, she “trapped” Leigh McMakin into marrying her. Leigh is happily reading the papers on the porch outside while she and I talk. As two elderly Jack Russells, named Mango and Panda, jump all over everything and everyone, McMakin’s elder daughter Celerie Kemble and her three children, Rascal, 17, Zinnia, 15, and Wick, 13, run between the tennis court and their rooms as they pack for their flight to New York.

With these youngsters, that makes six generations of Maddock blood in Palm Beach. (Celerie’s sister, Phoebe, and her four-year-old daughter, Daisy, visit regularly from their home in London, too.)

Many generations, so many stories.

After graduating from Brown University and serving as a lieutenant for the US Naval Reserve during World War II, McMakin’s father, Paul, settled in Palm Beach, where he married the former Allison Quigley, a tall blonde beauty from Chicago who had two young children from her previous marriage. Together, the couple had Mimi and two boys. After their divorce, three more children were born to Paul and his second wife. “So now we were eight,” McMakin recalls. “There were always people coming and going. Life was always easygoing. We fished off the dock, everybody rode their bicycles. I was taken to school by truck by the caretaker.”

The school day at Palm Beach Private was a far cry from today’s academic pressure cookers. “You’d be let out at twelve and you wouldn’t go back til three,” she says. “So, you could have a proper lunch at the club with your parents, play tennis, and then go back to school. Doesn’t that make more sense?”

Following the customs of the time, however, parents had their own lives after dark. “At night, it was ta-ta, bye-bye,” McMakin says. “Which I think we ought to go back to,” she adds, with a wink. “After seven o’clock, it ought to be, What children?”

For her debutante party at the Everglades Club in 1966, Lester Lanin and his orchestra entertained. “It was just beautiful,” she recalls. “I had no idea how privileged we were. It was just here.”

But from an early age she learned to show respect to her elders, despite their socioeconomic status: “My father treated everyone who worked for him at our house as though they were part of our family. They were friends. At Christmas, he would give everyone stockings; inside were shares of stock. Any time anyone wanted to sell, he would buy it back at the highest price it had ever been.”

A beloved figure in Palm Beach, he sang bass in a barbershop quartet and was frequently pulled over by cops for driving too slowly. “When he died [in 1985], the town basically closed down and everyone went to the church for his funeral,” she says.

While attending the all-girls Briarcliff College in Westchester, New York, there were many lessons to be learned—lots of them in Manhattan. “We’d go into the city and have drinks with gardenias in them at Trader Vic’s. On the train back, we’d be covered in gardenias.”

After their suitemate Lacey was befriended by Oleg Cassini, the girls’ social lives advanced: “We were all pretty blondes, now in limousines, going to cocktail parties way over our heads and to dinners with Salvador Dalí.”

The summer after she graduated, she and another suitemate, Jugsie, careened through Europe in a gleaming blue MGB convertible, a gift from Jugsie’s father, a top executive at Coca-Cola. Although they were given a nice allowance for the trip, much of their funds went to buying clothes and jewelry, leading them to sometimes sleep in the car or find other ways to economize. As McMakin tells it, “We would pull over in front of a local pub where there were nice young men. We’d lift up the hood and pull out a couple spark plugs. Of course, men want to help you fix your car. Then we’d get a free dinner.”

Post-college, McMakin’s father paid the rent on an apartment on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, though she was drawing a small salary working at Annacat, a fashionable boutique. “I had the best time. I went out every night and took two Aspirin before bed. Back then, you could see two or three men at the same time, and they wouldn’t know it. I had one beau for the week, and one for the weekend, and maybe one beau lived in Greenwich…”

It was through one of those men that she met William “Bill” Kemble, who she warmly refers to as “my first administration.” At McMakin’s behest, one of her beaux had drafted his buddy Bill to be a date for her sister. Plans changed when they all met at a cocktail party. “I kind of liked [Bill] and proceeded to break up with my boyfriend that night,” she recounts. “He’d grown up in a beautiful house outside Boston and had lovely parents. He drove a Porsche and had gone to Groton and Harvard. Everything sort of added up. I mean, come on!”

Newlywed life in 1979 New York began happily, with the birth of the couple’s first daughter, Celerie. But challenges followed. Bill disliked his job as a stockbroker and convinced McMakin to move to a cattle ranch in Colorado: “He loved it. I hated it. After a while, I said, ‘I can’t.’” They briefly returned to Manhattan, but this time it was McMakin who pulled the plug, after Bobo, her beloved cockapoo, was stolen. “That kind of killed New York for me,” she says sadly.

Soon after, her father suggested they move back to Palm Beach, into the vacant church. With the addition of a second girl, Phoebe, the young family embraced beach life, with touches of “Green Acres.” The twelve “lady” chickens they kept in the backyard were prohibited by local ordinances, but McMakin kept the neighbors, including the head of the town council, from squealing: “I bribed them with eggs.”

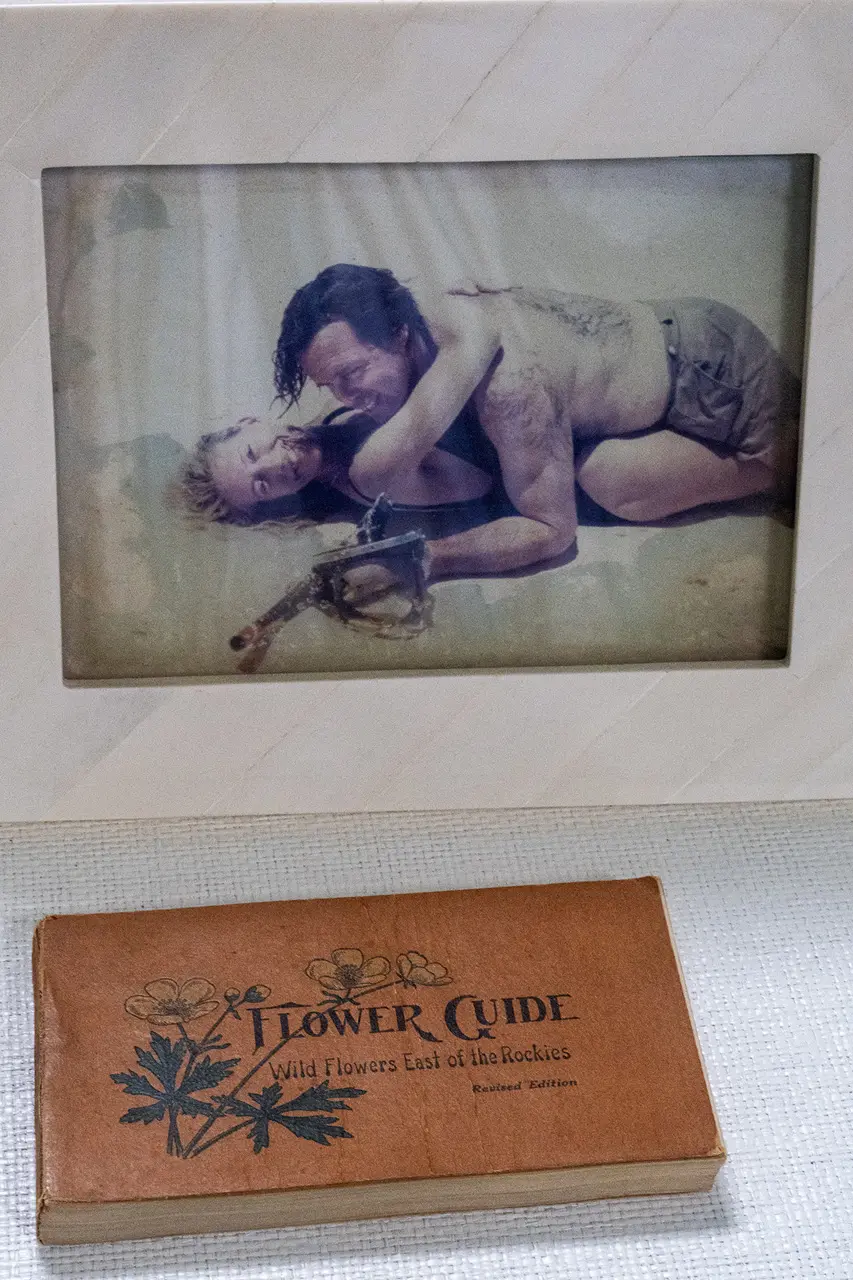

It was hardly all Robinson Crusoe, though, as the cover of the March 1988 issue of Town & Country attests. Photographed by Slim Aarons, a glamorous McMakin models a ruffled black-and-white Oscar de la Renta gown. The coverline: “Mimi Maddock Kemble: The Essence of Palm Beach.”

“What a lot of baloney!” she exclaims now, after I ask her to show me a framed copy in the hall, hanging among hundreds of family photos.

Around the time that issue appeared, the Kembles’ marriage was coming to an end. Yet the couple remained on the most amicable terms. “After we were divorced, I still did his laundry for three years,” she says. “We would have his birthday parties here and share Christmases. He was the sweetest man.” (Kemble died in 2022.)

Leigh McMakin, a California-born former investment manager who is an avid sailor and pilot, came into Mimi’s life one day when she was helping Phoebe man her lemonade stand on the Lake Trail behind their house: “A speedboat pulled up to the dock and one of the best-looking men you’ve ever seen in your life got out with a girl I knew.” After buying drinks, they invited Mimi to a party, where she got to chat with him. Not long afterwards, “I talked him into marrying me. Begged is the word for it. He was scared to death!” she roars.

McMakin waded into interior decorating when she was still single in New York. A girlfriend asked for help with her fledgling design business, and subsequently McMakin’s roommate, a lifelong New Yorker, began to introduce her to numerous ex-boyfriends—all well-off young men in need of help furnishing their starter homes. “What could be better?” she recalls. “I could go out with them and not marry them, but they all became future clients. It was great. They knew they didn’t have to feed me any longer. I charged them very little. And they were all just fabulous characters, good people, the kind of people your mother would say, Well done. Well, there were a few scoundrels—thank God. And that’s really how my business started.”

Following her move back to Palm Beach, McMakin landed a job working for Polly Jessup, the reigning queen of Palm Beach decorators. “She was the most elegant woman, always in a beautiful Mainbocher dress, her hair perfectly done,” McMakin remembers. “You’d know all of them,” McMakin answers when I ask about Jessup’s clientele—a who’s who of the American establishment that included Fords, Rockefellers, Mellons, and du Ponts.

“She was very detailed,” McMakin says of her boss at the time. “She had to be, because most of her clients had more than two or three houses. In the presentations, she would show them slides so they could remember, say, what bedroom number four at the plantation looked like. Of course, every few years, even if things were in good shape, it would still be time to change all the rooms.”

Jessup did have one client who turned out to be quite a shady character. As McMakin recalls, he paid all his bills in cash. “Which is sort of a fun story,” she says, recounting the time she and her colleague, Liz, picked up one of his payments—quite a bundle in a leather satchel. On the drive home, the girls were hungry, so they pulled over at the New England Oyster House in Fort Lauderdale, bringing the satchel in with them. When they got back to Palm Beach, Liz asked McMakin where the money was. Both thought the other had grabbed it. Speeding back to Fort Lauderdale, they found the untouched bag still under their table, just as the restaurant was closing. Later, the client was indicted for tax fraud. “‘Oh, Mrs. Jessup,’ I said to her after he went to jail, ‘You do the Mellons, and I think I’m doing the felons.’”

As the years went by, Jessup worked for her clients’ progeny. “What was nice was, she would do first, second, and third generations,” McMakin observes. Pausing a moment, she adds, “Which is what I’ve been doing all these years. I never thought I’d be in the business that long.”

Indeed, Kemble Interiors, which Mimi founded in 1982, has become the design firm of choice for Old Money families as well as the newer wealthy seeking to emulate that look, plus the occasional celebrity. The firm works internationally, but its stronghold is Palm Beach, as well as neighboring Hobe Sound. Over the years, Kemble Interiors has had its hand in nearly every storied estate designed by “the big five” historic architects of Palm Beach (Addison Mizner, John Volk, Maurice Fatio, Marion Sims Wyeth, and Howard Major). Its employees are split between offices in Palm Beach, London, and New York, where Celerie, a Harvard graduate, leads the team.

When it comes to her clients, McMakin is too discreet to name names. But Celerie recalls, “One time we went through the Forbes 400 and figured out that about a quarter of the families in it were clients. She is so modest about her accomplishments, but when I was growing up, she was the only working mom I knew. And she’s built a fantastic company that has probably put forty peoples’ kids through school here in Palm Beach.”

One client name that McMakin does let slip is Rod Stewart, for whom she has designed three houses. Which prompts another one of her funny stories, from a time when they were on a shopping trip in New York: “I’m waiting for him in the lobby of the St. Regis, and he appeared in full regalia–the Scottish hat, cape, and boots. I looked at him like, Are you serious? Of course, everybody in the lobby goes berserk. Then he says, ‘Mimi, where’s your car?’ I said, ‘I thought you had a car.’ So, oh God, I called my good friend Jugsie, who came over right away in her foul station wagon, which was full of her teenage sons’ horrible stuff. And off we went to buy antiques.”

In business, McMakin subscribes to the belief that the customer is always right. “I tell all the girls who come to work in our office: entitlement is absolutely not allowed here. I am thrilled you’ve been well educated, that you’re well traveled. But if you are going to work with our clients, whatever they’d like you to do, you do it with a smile. When a client has been horrible and really deserves to be spanked, I say, you’re not dating them. Just take a deep breath. Draw a nasty picture of them if you want. And I think it’s one of the reasons our company has been such a success.”

But Kemble Interiors isn’t for everyone, she knows. Notably, the subset of flashier new arrivals in town. “I do not have many of what I call “jet set” clients. Mine really want a home, which I’m really good at making. A big marble showplace is not what I do. They come to us because they know we’re not going to give them something that’s incorrect.”

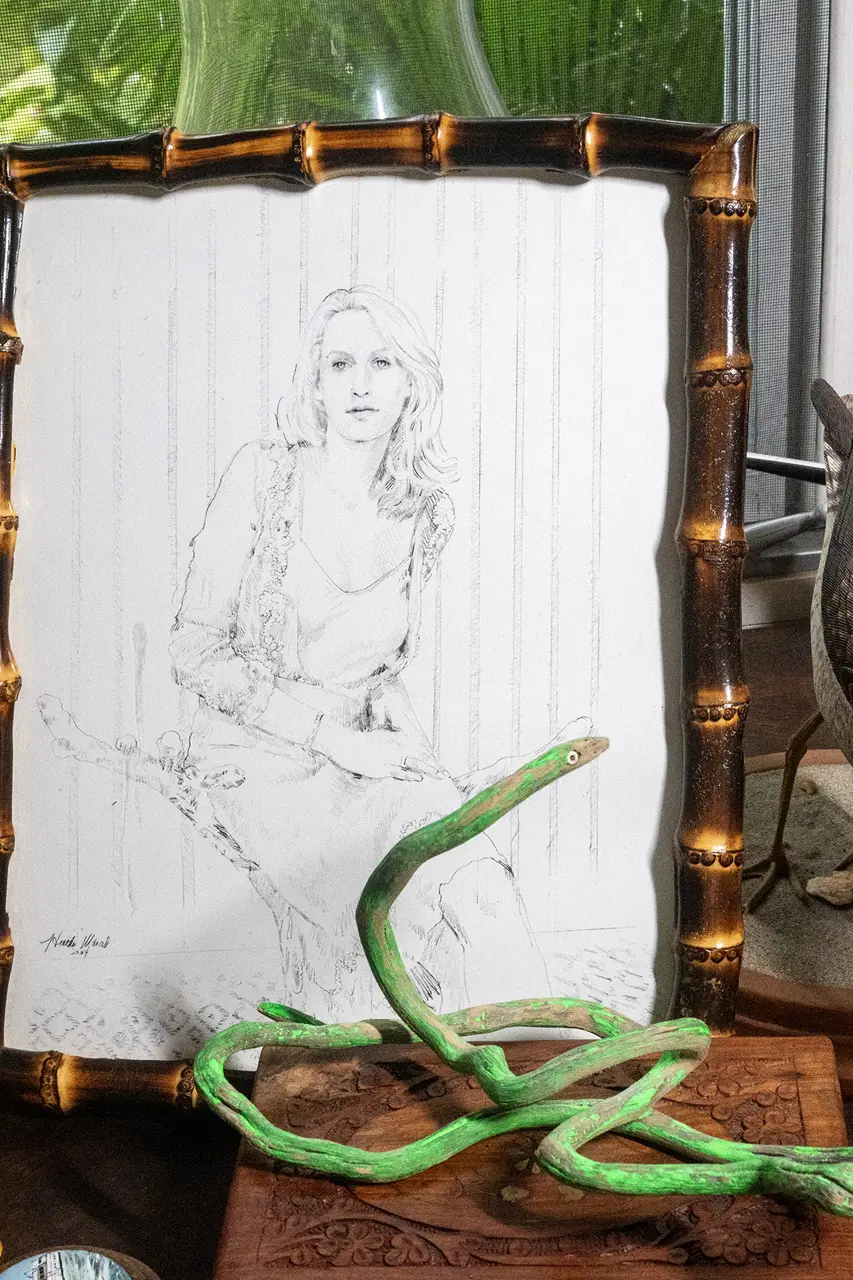

What is correct? How does one define “Palm Beach Style,” and McMakin’s own? “It’s whimsical, casually elegant, it has an inventiveness,” she explains. “We’ve established a look—it’s a look of comfort and whimsy and good things placed next to perhaps not such good things.”

What isn’t correct? “I don’t understand the necessity of bigness. If you are fortunate enough to love your husband, your children, and your house guests, why build so big? I think you get lost and lonely in these giant places. Why would you build something that looks like the mausoleums or parking garages that you see along the ocean today? Where’s the charm? They’ve forgotten charm, I think they’re just building for bigness now. They want to take what was a perfectly adequate house and expand it to the max.”

The subject is one that gets McMakin worked up. “I’ve just been here so long,” she adds. “I really care about keeping the cottage feeling, keeping kids on bikes, and not having it become Coconut Grove, [which is] my greatest fear.”

It might be a losing battle, she is aware. “Friends of mine just turned down a $300 million–dollar offer for their house,” she mentions, clearly referring to Jeff Bezos’s reported attempt to snap up Villa Artemis, the sandstone mansion designed in 1916 for Frederick and Amy Phipps Guest. Slim Aarons’s 1955 portrait of their daughter-in-law, C.Z. Guest, by the Grecian-style swimming pool, with her young son and their dogs, is one of the most iconic Palm Beach portraits of all time. As a girl, McMakin often dove into that pool. “I grew up thinking, That’s a pretty nice house. But $300 million! My friends and I, we just roll our eyes.”

Clubs have long been an integral part of Palm Beach life. Certainly, McMakin is an authority on this subject. “They come to town and the first thing they say is, ‘I want to join the club.’ For me, a club is a place where you take your kids to have lunch, play tennis, and swim. You didn’t join it to be recognized or because it’s a status symbol. A club to me is supposed to be a group of like-minded friends who’ve known each other for a while. I mean, I wouldn’t want to join a club if I didn’t know anybody in it.”

Professionally, clubs have been Kemble Interiors’ bread and butter. Over the years, the firm has decorated or refurbished more than 40 top-drawer country clubs across the country. “They know we’re not going to give them an Atlanta Ritz-Carlton,” McMakin says. “I’ve learned, don’t give them something that’s absolutely current. Go back a few years.”

In Palm Beach, McMakin has refurbished the clubs to which she belongs, including those inner sanctums, the Bath & Tennis and the Everglades. Working “in your own backyard,” as she describes it, presents extra challenges. “If they don’t like it, I’ll be tarred and feathered; they know where to find me.”

Comparatively few mortals will ever get to pass through those rarefied doors. But a few years ago, McMakin got to show the public what she is capable of when the owners of Palm Beach’s Colony Hotel asked Kemble Interiors to refresh the once stately but by then tired property. (As Kate Gubelmann remembers it, “That place was Mildew Manor.”)

Starting with a custom de Gournay botanical wallpaper, the lobby was transformed into a delightful and chic jungle, sparking a phenomenal revival for the hotel as well as for the Worth Avenue area. According to Vanity Fair, the Colony ranked as “the most Instagrammable hotel of 2020.”

“It’s a lovely old lady,” McMakin explains, speaking about the hotel and her approach to the project. “We embraced the fact that it’s not perfect. I just said, Let’s have some fun.”

The same could certainly be Mimi Maddock McMakin’s motto.